性别被誉为是“进化生物学中问题的皇后”,一直是生命科学领域的研究热点[1]。性别形成包括性别决定和性别分化,性别决定是指未分化的双向潜能性腺决定其是向卵巢方向发育,还是向精巢方向发育的过程。而性别分化是指未分化的双向潜能性腺发育为卵巢或者精巢,并出现第二性征的过程[2]。在水产动物中,揭示性别决定机制,可有助于实现对其进行性别控制,进而在实际育种工作中开展单性养殖。研究表明,单性养殖在提高群体生长率、控制繁殖速度、延长有效生产期、缩短育种时间等方面具有显著优势。目前,大多数脊椎动物的性别决定及性别分化机制已经得到较为全面的阐述,其性别决定机制也展现出复杂性和多样性。如哺乳动物的性别决定机制属于遗传型性别决定,其性别是由位于Y染色体上的SRY基因决定[3];多数爬行动物的性别决定属于温度依赖型性别决定,龟鳖类的性别会受到孵化温度的影响[4-5];而许多鱼类不仅受遗传因素决定,还受到环境因素的调控。如半滑舌鳎Cynoglossus semilaevis具有明显的性染色体,属于ZW/ZZ型,在温度过高或过低时雌鱼会发生性逆转[6-7],在遗传育种的过程中可通过人为改变环境因素得到伪雄鱼,然后与正常ZW雌鱼交配得到WW超雌鱼,从而实现全雌化育种。棘皮动物是继脊索动物的第二大类后口动物,在物种进化过程中处于重要位置。棘皮动物共分为海百合纲Crinoidea、海胆纲Echinoidea、海参纲Holothuroidea、海星纲Asteroidea和蛇尾纲Ophiuroidea 5个纲,现存共7 444种[8],主要分布于海洋中。其中海胆、海参、海星、海蛇尾具有较高食药用价值[9-11],海参和海胆更是被誉为“海产八珍”,经济价值极高[12-13],据2021年中国渔业统计年鉴显示,2020年中国海参和海胆养殖产量分别为196 564 t和7 952.53 t[14]。在海参产业中,中国北方以刺参Apostichopus japonicus为主,南方海参种类繁多,如糙海参Holothuria scabra、梅花参Thelenota ananas、花刺参Stichopus variegatus、白底辐肛参Actinopyga mauritiana和黑乳参Microthele nobilis等。海胆作为一种模式生物,除具有重要的经济价值外,还因胚胎透明、发育同步、孵化速度快、结构简单等特点,成为研究受精[15]、胚胎早期发育[16]、免疫[17]和进化[18]的一个良好模型。海胆的主要养殖种类有光棘球海胆Mesocentrotus nudus、中间球海胆Strongylocentrotus intermedius和马粪海胆Hemicentrotus pulcherrimus等。性腺是海胆唯一可食用部分,因此,早在20世纪初就有研究人员针对其性别决定及性腺发育展开相关研究。近年来,随着高通量测序、基因敲除、基因敲降、性控育种等生物技术的发展,棘皮动物的性别相关研究发展迅速。本文中,综述了有关棘皮动物性别决定和性别分化的遗传基础,以及性别控制育种在棘皮动物养殖中的应用、前景展望,以期推动经济棘皮动物性别控制育种工作的进程。

1 棘皮动物生殖策略

1.1 性别表型多样性

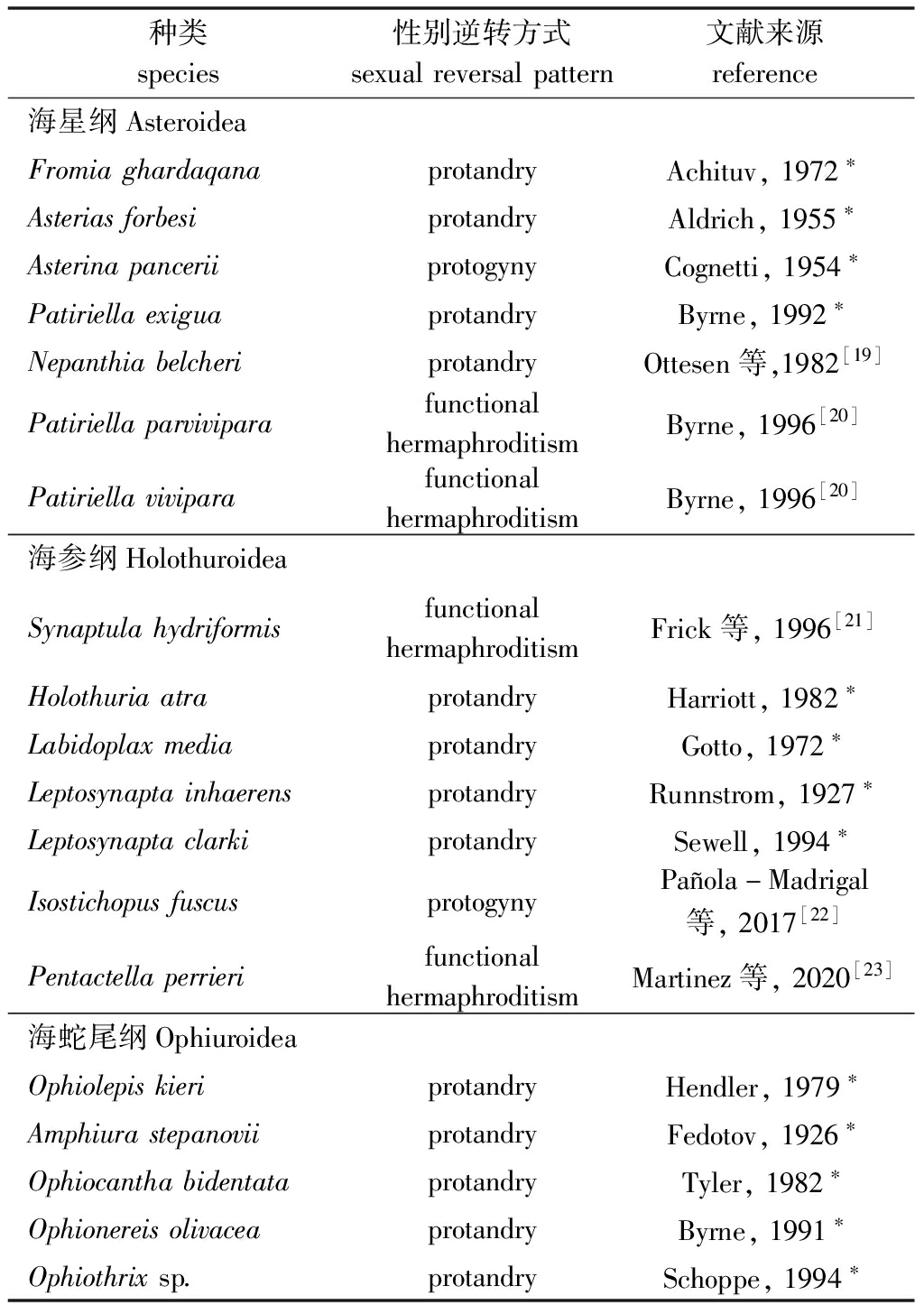

棘皮动物的性别表型呈现物种特异性和多样性。绝大多数棘皮动物属于雌雄异体,少数会在整个生活史中发生性逆转,存在雌雄同体现象(表1)。

表1 棘皮动物中雌雄同体种类及其性别逆转方式

Tab.1 Hermaphrodite species and sexual reversal patterns in Echinodermata

种类species性别逆转方式sexualreversalpattern文献来源reference海星纲AsteroideaFromiaghardaqanaprotandryAchituv,1972∗AsteriasforbesiprotandryAldrich,1955∗AsterinapanceriiprotogynyCognetti,1954∗PatiriellaexiguaprotandryByrne,1992∗NepanthiabelcheriprotandryOttesen等,1982[19]PatiriellaparviviparafunctionalhermaphroditismByrne,1996[20]PatiriellaviviparafunctionalhermaphroditismByrne,1996[20]海参纲HolothuroideaSynaptulahydriformisfunctionalhermaphroditismFrick等,1996[21]HolothuriaatraprotandryHarriott,1982∗LabidoplaxmediaprotandryGotto,1972∗LeptosynaptainhaerensprotandryRunnstrom,1927∗LeptosynaptaclarkiprotandrySewell,1994∗IsostichopusfuscusprotogynyPañola-Madrigal等,2017[22]PentactellaperrierifunctionalhermaphroditismMartinez等,2020[23]海蛇尾纲OphiuroideaOphiolepiskieriprotandryHendler,1979∗AmphiurastepanoviiprotandryFedotov,1926∗OphiocanthabidentataprotandryTyler,1982∗OphionereisolivaceaprotandryByrne,1991∗Ophiothrixsp.protandrySchoppe,1994∗

注:*原始参考文献来自Sewell(1994)[24]。

Note:* the original reference is from Sewell(1994)[24].

棘皮动物雌雄同体(hermaphroditism)可分为两类:功能性雌雄同体(functional hermaphroditism)和顺序性雌雄同体(sequential hermaphroditism)。功能性雌雄同体是指具备成熟精巢和卵巢,并能够同时产生精子和卵子的雌雄同体。顺序性雌雄同体是指阶段性的雌雄同体现象,即一个生物在特定的刺激之下转变性别的过程。Kubota[25]通过性腺组织学观察揭示了卵板步锚参Patinapta ooplax在繁殖季节可由雄性转变为雌性,之后再回转为雄性。贝氏尼斑海星Nepanthia belcheri既可进行无性生殖又可进行有性生殖,Ottesen等[19]通过性腺组织学观察发现,所有贝氏尼斑海星的性腺中均存在卵母细胞,这些性腺有的起卵巢作用,有的起精巢作用,发生无性生殖后,部分个体的卵巢会转变为精巢。此外,在雌雄异体的群体如紫色球海胆Strongylocentrotus purpuratus和暗色刺参Isostichopus fuscus中也会有个别个体表现为功能性的雌雄同体,其群体中性别比例往往会偏离1︰1[22,26]。

1.2 生殖对策多样性

在棘皮动物中,有两个与繁殖有关的生理学阈值:1)如果低于维持生物个体基本生存的最低营养需求,性腺将不会发育生长,而高于这个水平,性腺发育且体细胞有限生长(外部限制);2)性腺和体细胞的生长都在一定程度上受到获取食物能力的限制(内在限制)[27]。刺参在繁殖状态下存在多种生殖代价,如繁殖状态会抑制运动耐力和消化生理,提高代谢水平。但刺参也会有相应的适应策略,如行动可塑性与摄食食物的选择性可以适应运动耐力的减退和高能量的需求[28]。多数棘皮动物进行有性生殖,无性生殖的情况仅出现在少数海参、海星和海蛇尾中。除冠海星Stephanasterias albula是仅进行无性生殖的物种外[29],其余可以进行无性生殖的棘皮动物多为无性生殖与有性生殖交替进行。如地中海的Coscinasterias tenuispina海星兼具无性和有性生殖的能力,在长期进行无性繁殖的群体中其性腺仍然会保留生殖能力[30]。伯顿海燕Aquilonastra burtoni、多筛指海星Linckia multifora、辐蛇尾Ophiactis savignyi和Ophiocomella ophiactoides海星可以通过分裂中央盘或切开身体的某一只臂产生新个体[31-34]。黑海参Holothuria atra和黄疣海参H.hilla则可以将自己的身体扭断生长为两个新的个体[35-36]。目前,海胆中尚未发现无性生殖相关的报道。棘皮动物中天然单性生殖情况十分罕见。棘皮动物的性别表型及生殖对策的多样性,暗示着其性别决定及性别分化机制的多样性。

1.3 性别二态性

性别二态性是指同一物种雌雄两性间的性状差异[37]。大多数棘皮动物无明显的性别二态性,仅有少数种类可从外观分辨性别。Curunaria frondosa海参的雄性个体具有指状或可延伸的生殖乳突[38]。梅氏长海胆Echinometra mathaei雄性个体生殖乳突呈细长的管状,而雌性个体生殖乳突为短而圆的锥形突起[39]。也有些种类在个体大小方面存在显著的雌雄差异,如沙钱Echinarachnius parma、挎雄蛇尾Ophiodaphne formata雌性个体大于雄性[40-41]。在极端自然环境下长棘海星Acanthaster planci雄性个体为了延长寿命会牺牲其繁殖能力,从而导致雌性个体性腺质量大于雄性[42]。海参和海胆作为棘皮动物中重要养殖物种,较难从外表分辨雌雄,这也增加了遗传育种工作的难度。但海参和海胆中免疫力、激素含量等方面存在明显的性别差异[43]。此外,雌海胆性成熟时性腺会产生一种苦味氨基酸,使得雌性海胆不如雄性味道鲜美[44]。因此,在海参和海胆中开发单性养殖具有重要的应用前景。

2 棘皮动物性别决定和性别分化的遗传基础

通常性别决定可分为遗传性别决定(genetic sex determination, GSD)和环境性别决定(environmental sex determination, ESD)。遗传性别决定主要有基因性别决定和性染色体决定,性染色体又分为雄性异配性别决定和雌性异配性别决定;环境性别决定通常指生物的性别分化受到周围环境因素影响,如温度、pH、光照和周围群体密度等环境因素控制[45]。许多物种在性别决定中包含了遗传性别决定和环境性别决定两种机制,且这两种机制相互影响[6-7]。

2.1 染色体组成及异型性染色体

早在20世纪初,一些学者就针对棘皮动物的染色体展开了研究并试图揭示其染色体的带型。由于棘皮动物的染色体较小且紧聚,因此,进行染色体核型分析十分困难。棘皮动物的染色体数目在2n=36至2n=46之间,与其他物种相比,棘皮动物的染色体数目显示出了高度的保守性,但是,稳定的染色体数目并不一定意味着棘皮动物的进化过程中没有染色体演化[46]。性染色体通常被认为是从一对常染色体演化而来,进化过程中积累的突变使得原始的常染色体上的某个或某几个基因可以决定性别[47-48]。棘皮动物性染色体的研究一直是研究人员探究的热点和难点。早期研究中,Pinney[49]用切片法观察到Tripneustes ventricosus海胆染色体数目为30、32、33,并推测海胆的性别决定类型属于XO型。随后,通过Lytechinus pictus海胆人工孤雌生殖试验,发现存活个体都是雌性,由此推测,海胆的性别可能属于雄性异配型[50]。Colombera等[51]通过染色体观察推测,棘皮动物无可以区分的性染色体。但是,在紫色球海胆的胚胎时期进行切割可以获得同样性别的个体,意味着紫色球海胆性别可能是由染色体决定的[52]。直到1996年,Lipani等[53]在拟球海胆Paracentrotus lividus中发现了异型性染色体,并根据其核型分析提出拟球海胆性别决定机制属于XX/XY型。随后,在马粪海胆、紫色球海胆中也观察到了异型性染色体[54-55]。值得注意的是,Eno等[55]通过荧光原位杂交技术将雄性特异性表达的基因bindin定位到了紫色球海胆的一对同源染色体上,该染色体是否是性染色体还有待验证。

2.2 性别相关分子标记的挖掘

目前,针对棘皮动物性别决定和性别分化的研究还处于起步阶段。近年来,随着高通量测序技术的迅猛发展,紫色球海胆、长棘海星和刺参相继完成了全基因组测序工作[56-58],这为棘皮动物性别标记基因的挖掘提供了海量的数据。目前,针对棘皮动物性别决定和性别分化的研究主要集中在性腺发育、配子发生及性腺转录组测序等层面。海参中性别分子标记相关报道甚少,近期,魏金亮等[59]基于全基因组水平经过同源比对鉴定出dmrt1、nodal、foxl2、piwi等多个与性腺发育相关的基因,值得注意的是,nodal在卵巢中特异表达。此外,DNMT3作为一种DNA甲基转移酶,在刺参的精巢中特异表达,暗示着刺参的性别发生可能与甲基化有关[60]。与海参相比,海胆中针对性别分子标记挖掘的工作相对较多,如在光棘球海胆卵巢转录组数据库中鉴定出8个与卵巢成熟相关的基因,包括Mos、Cdc20、Rec8、YP30、cytochrome P450 2U1、ovoperoxidase、proteoliaisin和rendezvin[61],47个雄性特异小分子RNA(MicroRNAs)和51个雌性特异小分子RNA[62]。此外,一些进化上高度保守的性别标记基因也通过高通量测序工作得以挖掘。相关学者通过性腺转录组测序在光棘球海胆中鉴定出多个性别差异表达基因,其中包括雄性特异表达基因dmrt1[63]、生殖细胞标记基因nanos2[64]与piwi[65],以及与卵巢发育和维持相关的基因foxl2[66]等。值得注意的是,foxl2在光棘球海胆精巢中高表达,与脊椎动物同源的amh在卵巢中的表达量大于精巢,这与在脊椎动物中的表达情况相反,意味着其可能在棘皮动物性别决定和性别分化过程中发挥不同的作用[67]。本实验室最新研究表明,通过简化基因组测序技术,在刺参中鉴定出1个雄性特异DNA分子标记,可以快速、精准地鉴定刺参生理性别,并推测刺参的性别决定应该是XX/XY型[68]。采用同样的方法,在光棘球海胆开发出3个可用于性别鉴定的雌性特异DNA分子标记,并推测光棘球海胆的性别决定类型为ZW/ZZ型[69]。

3 性别控制育种技术在棘皮动物养殖中的应用

3.1 人工诱导雌核发育

天然单性种群多采用雌核生殖、孤雌生殖或杂种生殖的方法繁衍后代[70]。海胆性腺是唯一可食用部分,培养不育的三倍体海胆可以抑制配子发生,延长上市时间。为了达到上述目的,常亚青等[71]率先提出利用静水压法获得四倍体海胆,之后与正常的二倍体杂交,最终获得三倍体海胆。随后,Böttger等[72]采用另外一种完全不同的方式培育三倍体海胆,即先把两个成熟卵融合,再用高度稀释的精子使卵融合产物受精。多倍体育种过程中会由于无法正常进行减数分裂而不能正常繁育后代[73],这正是多倍体育种面临的主要障碍,解决方式之一就是人工诱导雌核发育。雌核发育是水产经济动物种质改良、建立全雌化后代、缩短育种年限的有效方法,且已经成功运用在多种水产养殖品种。例如,利用热休克或静水压法抑制卵母细胞第二极体排出诱导虹鳟雌核发育[74],使用电刺激诱导栉孔扇贝Chlamys farreri雌核发育[75]。与鱼类和贝类不同,海胆成熟卵的第一极体和第二极体在卵巢中已排出,因此,无法通过抑制第一极体和第二极体的方式诱导雌核发育二倍体,只能通过抑制第一次卵裂诱导雌核发育二倍体[76]。早在1975年,Brandriff等[50]就使用NH4OH和离子载体A23187激活海胆成熟卵,随后进行二次高渗处理,成功诱导Lytechinus pictus海胆雌核发育并最终获得了成年的雌性二倍体。尽管此方面的研究开始较早,但棘皮动物单性养殖、多倍体育种的案例仍鲜有报道,相关研究中,曹学彬等[77]通过紫外线照射灭活精子,随后采用热休克处理激活的卵子进而抑制其第一次卵裂使染色体加倍,获得了海胆雌核发育胚胎。

3.2 性激素水平与性腺发育

性激素,尤其是雌二醇和睾酮在脊椎动物性别分化的过程中行使重要功能[78-79]。近年来,针对无脊椎动物性激素的研究成了热点,且多集中在性激素种类的鉴定及对基因表达的影响两个层面。Botticelli等[80]利用蒸馏和层析等方法证实,巨紫球海胆Strongylocentrotus franciscanus性腺中存在雌激素,其中,17-β雌二醇活性最强;Sclerasterias mollis海星的幽门盲肠可以合成17-β雌二醇[81];在红海盘车Asterias rubens的幽门盲肠与性腺中均检测到了雌酮和黄体酮,且两者的含量呈季节性变化,卵黄开始形成时黄体酮含量会显著升高,由此推测,黄体酮可能参与卵母细胞的发生[82]。此外,在胚胎发育早期用雌酮处理马粪海胆与光棘球海胆,MYP基因表达会受到显著的抑制[83]。

3.3 性别相关基因与性腺发育

性别决定基因是在性腺发育的早期瞬时表达并指导个体朝不同性别发育的基因,哺乳动物的Sry基因、红鳍东方鲀Takifugu rubripes的Amhr2基因[84]、非洲爪蟾Xenopus laevis的DM-W基因等均为性别决定基因[85]。采用基因敲除或基因敲降技术缺失或沉默性别决定基因,会使该物种发生性反转,进而产生遗传背景与性别表型不一致的现象。例如,在青鳉Oryzias latipes中注射Dmy基因的反义RNA,会影响Gsdf、Sox9a2和Rspo1基因等的表达,同时会使雄鱼发生性逆转[86]。目前,棘皮动物中尚未有性别决定基因的报道,也无利用基因敲除获得基因缺失的成体案例。但利用RNA干扰等技术使性别相关基因表达沉默,在海参和海胆中均有报道。光棘球海胆中,通过向体腔内注射靶向特异的双链RNA(dsRNA)可以成功敲降靶基因nanos2,同时降低boule和foxl2基因表达量[64]。在刺参中,运用同样的方法也可以降低靶基因及性腺发育有关基因表达[87]。这些研究为在成体水平研究棘皮动物性别标记基因与性腺发育之间的关系奠定了基础。

4 未来重点研究方向

近年来,棘皮动物性别决定与分化的研究已经取得了一些初步的进展,特别是全基因组、转录组、蛋白质组及代谢组等大数据信息的不断完善,为棘皮动物性别决定的基础研究提供了海量的数据支撑,荧光原位杂交、染色体切割、基因敲降、基因敲除等技术的快速发展也为在棘皮动物中研究基因的定位及功能奠定了基础。但是棘皮动物性别决定和性别分化的机制仍不明确,未来应在以下方面开展深入研究:

1)性染色体的确定。尽管在一些棘皮动物的物种中,通过显微观察等技术观察到了异型染色体,但棘皮动物中是否存在性染色体仍不明确。后期可改进染色体制备技术,尽量避免染色体丢失,并结合荧光原位杂交技术把性别连锁基因定位在染色体上,随后通过显微切割、单染色体测序等工作分离鉴定棘皮动物的性染色体。

2)性别连锁分子标记的开发与应用。多数棘皮动物不具备性别二态型,这大大增加了遗传育种工作的难度。可以通过简化基因组测序及构建遗传连锁图谱等开发稳定的性别特异的分子标记,如SNP位点,以应用于分子标记辅助育种。

3)基因编辑技术的应用。随着高通量测序的蓬勃发展,棘皮动物如海参、海胆中都鉴定出了大量与性腺发育相关的基因,接下来如何揭示基因功能成为重中之重。海参、海胆研究中都有胚胎发育时期成功进行基因敲除的案例,由于成活率低,基因敲除的胚胎较难发育到成体阶段。针对基因敲除难以进行的现状,可以使用RNA干扰、慢病毒干扰等试验技术研究棘皮动物性别相关基因的功能。

4)性激素诱导单性养殖。利用性激素诱导使脊椎动物发生性转变是使用最为广泛的单性育种技术,在棘皮动物中是否也可进行类似操作尚有待验证。目前,在多种棘皮动物中都鉴定出了与棘皮动物同源的性激素,如雌二醇和睾酮,随后,可以采用浸泡、口服、注射等方法用性激素诱导棘皮动物,开发单性养殖。

5)多倍体良种培育。利用三倍体不育的特性,培育三倍体刺参。三倍体刺参能有效限制性腺发育与体壁发育的营养竞争,进而显著提高刺参的产量。此外,多倍体的生殖细胞会明显大于同龄的二倍体生殖细胞,培育多倍体的海胆,会提高生殖腺的产量。培育三倍体可以先使用物理方法或化学方法在胚胎发育时期抑制二倍体胚胎卵裂,进而诱导四倍体产生,随后与正常二倍体杂交得到三倍体。

[1] 梅洁,桂建芳.鱼类性别异形和性别决定的遗传基础及其生物技术操控[J].中国科学(生命科学),2014,44(12):1198-1212.

MEI J,GUI J F.Genetic basis and biotechnological manipulation of sexual dimorphism and sex determination in fish[J].Science China(Life Sciences),2014,44(12): 1198-1212.(in Chinese)

[2] 杨东,余来宁.鱼类性别与性别鉴定[J].水生生物学报,2006,30(2):221-226.

YANG D,YU L.Sex and sex identification of fish[J].Acta Hydrobiologica Sinica,2006,30(2): 221-226.(in Chinese)

[3] KOOPMAN P,GUBBAY J,VIVIAN N,et al.Male development of chromosomally female mice transgenic for Sry[J].Nature,1991,351(6322):117-121.

[4] BULL J J,VOGT R C.Temperature-dependent sex determination in turtles[J].Science,1979,206(4423): 1186-1188.

[5] BULL J J,VOGT R C.Temperature-sensitive periods of sex determination in emydid turtles[J].Journal of Experimental Zoology,1981,218(3):435-440.

[6] CHEN S L,TIAN Y S,YANG J F,et al.Artificial gynogenesis and sex determination in half-smooth tongue sole(Cynoglossus semilaevis)[J].Marine Biotechnology,2009,11(2):243-251.

[7] SHAO C W,LI Q Y,CHEN S L,et al.Epigenetic modification and inheritance in sexual reversal of fish[J].Genome Research,2014,24(4):604-615.

[8] HORTON T,KROH A,AHYONG S,et al.World register of marine species(WoRMS):WoRMS Editorial Board[DB/OL].2020.[2020-07-29].http://www.marinespecies.org.

[9] 常亚青,丁君,宋坚,等.海参、海胆生物学研究与养殖[M].北京:海洋出版社,2004.

CHANG Y Q,DING J,SONG J,et al.Biological research and culture of sea cucumber and sea urchin[M].Beijing: China Ocean Press,2004.(in Chinese)

[10] CHEN S G,XUE C H,YIN L A,et al.Comparison of structures and anticoagulant activities of fucosylated chondroitin sulfates from different sea cucumbers[J].Carbohydrate Polymers,2011,83(2): 688-696.

[11] 房景辉,张继红,蒋增杰,等.北黄海3种常见蛇尾的主要营养成分分析[J].渔业科学进展,2015,36(6):17-21.

FANG J H,ZHANG J H,JIANG Z J,et al.The analysis of nutrient components of three brittle star species in the North Yellow Sea[J].Progress in Fishery Sciences,2015,36(6): 17-21.(in Chinese)

[12] CHEN J X.Overview of sea cucumber farming and sea ranching practices in China[J].SPC Beche-de-Mer Information Bulletin,2003,18:18-23.

[13] 高绪生,常亚青.中国经济海胆及其增养殖[M].北京:中国农业出版社,1999.

GAO X S,CHANG Y Q.Culture and enhancement of economic sea urchin in Chinese[M].Beijing:China Agriculture Press,1999.(in Chinese)

[14] 农业农村部渔业渔政管理局,全国水产技术推广总站,中国水产学会.2021中国渔业统计年鉴[M].北京:中国农业出版社,2021.

Bureau of Fisheries of the Ministry,Agriculture and Rural Affairs,National Fisheries Technology Extension Center,China Society of Fisheries.2020 China fishery statistical yearbook[M].Beijing:China Agriculture Press,2020.(in Chinese)

[15] CHUN J T,LIMATOLA N,VASILEV F,et al.Early events of fertilization in sea urchin eggs are sensitive to actin-binding organic molecules[J].Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications,2014,450(3): 1166-1174.

[16] JULIANO C E,YAJIMA M,WESSEL G M.Nanos functions to maintain the fate of the small micromere lineage in the sea urchin embryo[J].Developmental Biology,2010,337(2):220-232.

[17] KOBER K M,BERNARDI G.Phylogenomics of strongylocentrotid sea urchins[J].BMC Evolutionary Biology,2013,13:88.

[18] BRANCO P C,FIGUEIREDO D A L,DA SILVA J R M C.New insights into innate immune system of sea urchin:coelomocytes as biosensors for environmental stress[J].Oa Biology,2014,2(1):2.

[19] OTTESEN P O,LUCAS J S.Divide or broadcast:interrelation of asexual and sexual reproduction in a population of the fissiparous hermaphroditic sea star Nepanthia belcheri(Asteroidea:Asterinidae)[J].Marine Biology,1982,69(3):223-233.

[20] BYRNE M.Viviparity and intragonadal cannibalism in the diminutive sea stars Patiriella vivipara and P.parvivipara(family Asterinidae)[J].Marine Biology,1996,125(3):551-567.

[21] FRICK J E,RUPPERT E E,WOURMS J P.Morphology of the ovotestis of Synaptula hydriformis(Holothuroidea,Apoda):an evolutionary model of oogenesis and the origin of egg polarity in echinoderms[J].Invertebrate Biology,1996,115(1):46-66.

[22] PA OLA-MADRIGAL A,CALDERON-AGUILERA L E,AGUILAR-CRUZ C A,et al.Reproductive cycle of the sea cucumber(Isostichopus fuscus)and its relationship with oceanographic variables at its northernmost distribution site[J].Revista de Biologia Tropical,2017,65(sup 1):S180-S196.

OLA-MADRIGAL A,CALDERON-AGUILERA L E,AGUILAR-CRUZ C A,et al.Reproductive cycle of the sea cucumber(Isostichopus fuscus)and its relationship with oceanographic variables at its northernmost distribution site[J].Revista de Biologia Tropical,2017,65(sup 1):S180-S196.

[23] MARTINEZ M I,ALBA-POSSE E J,LAURETTA D,et al.Reproductive features in the sea cucumber Pentactella perrieri(Ekman,1927)(Holothuroidea:Cucumariidae):a brooding hermaphrodite species from the southwestern Atlantic Ocean[J].Polar Biology,2020,43(9):1383-1389.

[24] SEWELL M A.Small size,brooding,and protandry in the apodid sea cucumber Leptosynapta clarki[J].The Biological Bulletin,1994,187(1):112-123.

[25] KUBOTA T.Reproduction in the apodid sea cucumber Patinapta ooplax:semilunar spawning cycle and sex change[J].Zoological Science,2000,17(1):75-81.

[26] GONOR J J.Sex ratio and hermaphroditism in Oregon intertidal populations of the echinoid Strongylocentrotus purpuratus[J].Marine Biology,1973,19(4):278-280.

[27] LAWRENCE J M.Functional biology of echinoderms[M].London:Croom Helm,1987.

[28] 茹小尚.刺参生殖代价与适应机制研究[D].青岛:中国科学院大学(中国科学院海洋研究所),2018.

RU X S.Research of cost of reproduction and adaptation strategy of sea cucumber Apostichopus japonicus[D].Qingdao: University of Chinese Academy of Sciences(Institute of Oceanology,Chinese Academy of Sciences),2018.(in Chinese)

[29] MLADENOV P V,CARSON S F,WALKER C W.Reproductive ecology of an obligately fissiparous population of the sea star Stephanasterias albula stimpson[J].Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology,1986,96(2):155-175.

[30] GARCIA-CISNEROS A,PÉREZ-PORTELA R,WANGENSTEEN O S,et al.Hope springs eternal in the starfish gonad:preserved potential for sexual reproduction in a single-clone population of a fissiparous starfish[J].Hydrobiologia,2017,787(1):291-305.

[31] ACHITUV Y,SHER E.Sexual reproduction and fission in the sea star Asterina burtoni from the Mediterranean coast of Israel[J].Bulletin of Marine Science,1991,48(3):670-678.

[32] EDMONDSON C H.Autotomy and regeneration in Hawaiian starfishes[J].Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum,1935,11(8):3-20.

[33] MCGOVERN T.Patterns of sexual and asexual reproduction in the brittle star Ophiactis savignyi in the Florida Keys[J].Marine Ecology Progress Series,2002,230:119-126.

[34] MLADENOV P V,EMSON R H,COLPIT L V,et al.Asexual reproduction in the west Indian brittle star Ophiocomella ophiactoides(H.L.Clark)(Echinodermata:Ophiuroidea)[J].Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology,1983,72(1):1-23.

[35] THORNE B V,ERIKSSON H,BYRNE M.Long term trends in population dynamics and reproduction in Holothuria atra(Aspidochirotida)in the southern Great Barrier Reef:the importance of asexual and sexual reproduction[J].Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom,2012,93(4):1067-1072.

[36] DOLMATOV I Y.Asexual reproduction in holothurians[J].Scientific World Journal,2014.doi.org/10.1155/2014/527234.

[37] LEINONEN T,CANO J M,MERIL J.Genetic basis of sexual dimorphism in the three spine stickleback Gasterosteus aculeatus[J].Heredity,2011,106(2):218-227.

J.Genetic basis of sexual dimorphism in the three spine stickleback Gasterosteus aculeatus[J].Heredity,2011,106(2):218-227.

[38] MONTGOMERY E M,FERGUSON-ROBERTS J M,GIANASI B L,et al.Functional significance and characterization of sexual dimorphism in holothuroids[J].Invertebrate Reproduction & Development,2018,62(4):191-201.

[39] TAHARA Y,OKADA M.Normal development of secondary sexual characters in the sea urchin,Echinometra mathaei[J].Publications of the Seto Marine Biological Laboratory,1968,16(1):41-50.

[40] HAMEL J F,HIMMELMAN J H.Sexual dimorphism in the sand dollar Echinarachnius parma[J].Marine Biology,1992,113(3):379-383.

[41] BARNES R D.Invertebrate zoology[M].Philadelphia:Saunders College,1980.

[42] STUMP R J.Age determination and life-history characteristics of Acanthaster planci(L.)(Echinodermata:Asteroidea)[M].Townsville:James Cook University,1994.

[43] JIANG J W,ZHOU Z C,DONG Y,et al.Comparative analysis of immunocompetence between females and males in the sea cucumber Apostichopus japonicus[J].Fish & Shellfish Immunology,2017,63:438-443.

[44] MURATA Y,SATA N U,YOKOYAMA M,et al.Determination of a novel bitter amino acid,pulcherrimine,in the gonad of the green sea urchin Hemicentrotus pulcherrimus[J].Fisheries Science,2001,67(2):341-345.

[45] JANZEN F J,PHILLIPS P C.Exploring the evolution of environmental sex determination,especially in reptiles[J].Journal of Evolutionary Biology,2006,19(6):1775-1784.

[46] DUFFY L,SEWELL M A,MURRAY B G.Chromosome number and chromosome variation in embryos of Evechinus chloroticus(Echinoidea:Echinometridae):is there conservation of chromosome number in the phylum Echinodermata? new findings and a brief review[J].Invertebrate Reproduction & Development,2007,50(4):219-231.

[47] CHARLESWORTH D,CHARLESWORTH B,MARAIS G.Steps in the evolution of heteromorphic sex chromosomes[J].Heredity,2005,95(2):118-128.

[48] BELLOTT D W,SKALETSKY H,PYNTIKOVA T,et al.Convergent evolution of chicken Z and human X chromosomes by expansion and gene acquisition[J].Nature,2010,466(7306):612-616.

[49] PINNEY E.A study of the chromosomes of Hippono⊇ esculenta and Moira atropos[J].The Biological Bulletin,1911,21(3):168-186.

[50] BRANDRIFF B,HINEGARDNER R T,STEINHARDT R.Development and life cycle of the parthenogenetically activated sea urchin embryo[J].Journal of Experimental Zoology,1975,192(1):13-23.

[51] COLOMBERA D,VENIER G.I cromosomi degli echinodermi[J].Caryologia,1976,29(1):35-40.

[52] CAMERON R A,LEAHY P S,DAVIDSON E H.Twins raised from separated blastomeres develop into sexually mature Strongylocentrotus purpuratus[J].Developmental Biology,1996,178(2):514-519.

[53] LIPANI C,VITTURI R,SCONZO G,et al.Karyotype analysis of the sea urchin Paracentrotus lividus(Echinodermata):evidence for a heteromorphic chromosome sex mechanism[J].Marine Biology,1996,127(1):67-72.

[54] 常亚青,曹洁,张彦娇,等.马粪海胆的染色体制备及组型分析[J].大连水产学院学报,2006,21(3):247-250.

CHANG Y Q,CAO J,ZHANG Y J,et al.The chromosome preparation and karyotype analysis of sea urchin Hemicentrotus pulcherrimus[J].Journal of Dalian Fisheries University,2006,21(3): 247-250.(in Chinese)

[55] ENO C C,BÖTTGER S A,WALKER C W.Methods for karyotyping and for localization of developmentally relevant genes on the chromosomes of the purple sea urchin,Strongylocentrotus purpuratus[J].The Biological Bulletin,2009,217(3):306-312.

[56] SODERGREN E,WEINSTOCK G M,DAVIDSON E H,et al.The genome of the sea urchin Strongylocentrotus purpuratus[J].Science,2006,314(5801):941-952.

[57] HALL M R,KOCOT K M,BAUGHMAN K W,et al.The crown-of-thorns starfish genome as a guide for biocontrol of this coral reef pest[J].Nature,2017,544(7649):231-234.

[58] ZHANG X J,SUN L N,YUAN J B,et al.The sea cucumber genome provides insights into morphological evolution and visceral regeneration[J].PLoS Biology,2017,15(10):e2003790.

[59] 魏金亮,崔洲平,张建.基于全基因组筛选刺参性腺发育相关基因及其表达特性分析[C].南宁:中国水产学会范蠡学术大会,2019:46.

WEI J L,CUI Z P,ZHANG J.Whole-genome screening and expression analysis of gonadal development-related genes in the sea cucumber,Apostichopus japonicus[C].Nanning:Fanli Academic Conference of China Society of Fisheries,China Society of Fisheries,2019:46.(in Chinese)

[60] HONG H H,LEE S G,JO J,et al.Identification and sequencing of the gene encoding DNA methyltransferase 3(DNMT3)from sea cucumber,Apostichopus japonicus[J].Molecular Biology Reports,2019,46(4):3791-3800.

[61] JIA Z Y,WANG Q A,WU K K,et al.De novo transcriptome sequencing and comparative analysis to discover genes involved in ovarian maturity in Strongylocentrotus nudus[J].Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part D:Genomics and Proteomics,2017,23:27-38.

[62] MI X,WEI Z L,ZHOU Z C,et al.Identification and profiling of sex-biased microRNAs from sea urchin Strongylocentrotus nudus gonad by Solexa deep sequencing[J].Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part D:Genomics and Proteomics,2014,10:1-8.

[63] CUI Z,ZHANG J,SUN Z,et al.Testis-specific expression pattern of dmrt1 and its putative regulatory region in the sea urchin(Mesocentrotus nudus)[J].Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part B:Biochemistry and Molecular Biology,2021.doi:10.1016/j.cbpb.2021.110668.

[64] ZHANG J,HAN X,WANG J,et al.Molecular cloning and sexually dimorphic expression analysis of nanos2 in the sea urchin,Mesocentrotus nudus[J].International Journal of Molecular Sciences,2019,20(11):2705.

[65] 王锦,张健,刘炳正,等.光棘球海胆seali基因克隆及表达特性分析[J].水生生物学报,2020,44(3):534-540.

WANG J,ZHANG J,LIU B Z,et al.Cloning and expression analysis of the seali gene in Mesocentrotus nudus[J].Acta Hydrobiologica Sinica,2020,44(3):534-540.(in Chinese)

[66] CRISPONI L,DEIANA M,LOI A,et al.The putative forkhead transcription factor FOXL2 is mutated in blepharophimosis/ptosis/epicanthus inversus syndrome[J].Nature Genetics,2001,27(2):159-166.

[67] SUN Z H,ZHANG J,ZHANG W J,et al.Gonadal transcriptomic analysis and identification of candidate sex-related genes in Mesocentrotus nudus[J].Gene,2019,698:72-81.

[68] WEI J L,COING J J,SUN Z H,et al.A rapid and reliable method for genetic sex identification in sea cucumber,Apostichopus japonicus[J].Aquaculture,2021.doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2021.737021.

[69] CUI Z,ZHANG J,SUN Z,et al.Identification of sex-specific markers through 2b-RAD sequencing in the sea urchin(Mesocentrotus nudus)[J].Frontiers in Genetics,2021.doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2021.717538.

[70] 桂建芳,周莉.多倍体银鲫克隆多样性和双重生殖方式的遗传基础和育种应用[J].中国科学(生命科学),2010,40(2):97-103.

GUI J F,ZHOU L.Genetic basis and breeding application on clonal diversity and dual reproduction modes in polyploid Carassius auratus gibelio[J].Science China(Life Sciences),2010,40(2): 97-103.(in Chinese)

[71] 常亚青,于明治,曹学彬,等.海胆四倍体苗种的诱导和培育方法:中国,CN101103707A[P].2008-01-16.

CHANG Y Q,YU M Z,CAO X B,et al.Induction and cultivation of sea urchin tetraploid seedlings:CN101103707[P].2008-01-16.(in Chinese)

[72] BÖTTGER S A,ENO C C,WALKER C W.Methods for generating triploid green sea urchin embryos:an initial step in producing triploid adults for land-based and near-shore aquaculture[J].Aquaculture,2011,318(1/2):199-206.

[73] DENIZ B.Chromosome association in allotetraploid interspecific hybrid ryegrass and parental species[J].Turkish Journal of Agriculture and Forestry,2002,26(1):1-9.

[74] CHOURROUT D,QUILLET E.Induced gynogenesis in the rainbow trout:sex and survival of progenies production of all-triploid populations[J].Theoretical and Applied Genetics,1982,63(3):201-205.

[75] 商文聪,赵泊淞,陈亮,等.电刺激诱导栉孔扇贝雌核发育的相关参数的筛选[J].中国海洋大学学报,2012,42(10):65-70.

SHANG W C,ZHAO B S,CHEN L,et al.Determination of the electrical pulsing parameters inducing the gynogenesis of Chlamys farreri[J].Periodical of Ocean University of China,2012(10):65-70.(in Chinese)

[76] NAKASHIMA S,KATO K H.Centriole behavior during meiosis in oocytes of the sea urchin Hemicentrotus pulcherrimus[J].Development,Growth & Differentiation,2001,43(4):437-445.

[77] 曹学彬,丁君,常亚青.人工诱导马粪海胆雌核发育的早期胚胎发育及细胞学观察[J].大连水产学院学报,2008,23(1):1-7.

CAO X B,DING J,CHANG Y Q.The early embryonic development and the cytological observation of gynogenesis in sea urchin Hemicentrotus pulcherrimus artificially induced[J].Journal of Dalian Fisheries University,2008,23(1):1-7.(in Chinese)

[78] PASK A J.A role for estrogen in somatic cell fate of the mammalian gonad[J].Chromosome Research,2012,20(1):239-245.

[79] LAIRD M,THOMSON K,FENWICK M,et al.Androgen stimulates growth of mouse preantral follicles in vitro:interaction with follicle-stimulating hormone and with growth factors of the TGF β superfamily[J].Endocrinology,2017,158(4):920-935.

[80] BOTTICELLI C R,HISAW F L,WOTIZ H H.Estrogens and Progesterone in the sea urchin(Strongylocentrotus franciscanus)and pecten(Pecten hericius)[J].Experimental Biology & Medicine,1961,106(4):887-889.

[81] XU R A,BARKER M F.Annual changes in the steroid levels in the ovaries and the pyloric caeca of Sclerasterias mollis(Echinodermata:Asteroidea)during the reproductive cycle[J].Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A:Physiology,1990,95(1):127-133.

[82] SCHOENMAKERS H J N,DIELEMAN S J.Progesterone and estrone levels in the ovaries,pyloric caeca,and perivisceral fluid during the annual reproductive cycle of starfish,Asterias rubens[J].General and Comparative Endocrinology,1981,43(1):63-70.

[83] KIYOMOTO M,KIKUCHI A,MORINAGA S,et al.Exogastrulation and interference with the expression of major yolk protein by estrogens administered to sea urchins[J].Cell Biology and Toxicology,2008,24(6):611-620.

[84] KAMIYA T,KAI W,TASUMI S,et al.A trans-species missense SNP in Amhr2 is associated with sex determination in the tiger pufferfish,Takifugu rubripes(fugu)[J].PLoS Genetics,2012,8(7):e1002798.

[85] YOSHIMOTO S,IKEDA N,IZUTSU Y,et al.Opposite roles of DMRT1 and its W-linked paralogue,DM-W,in sexual dimorphism of Xenopus laevis:implications of a ZZ/ZW-type sex-determining system[J].Development,2010,137(15):2519-2526.

[86] CHAKRABORTY T,ZHOU LINYAN,CHAUDHARI A,et al.Dmy initiates masculinity by altering Gsdf/Sox9a2/Rspo1 expression in medaka(Oryzias latipes)[J].Scientific Reports,2016,6:19480.

[87] SUN Z H,WEI J L,CUI Z P,et al.Identification and functional characterization of piwi1 gene in sea cucumber,Apostichopus japonicas[J].Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part B: Biochemistry and Molecular Biology,2021,252:110536.