从卵生到胎生的过渡是生命史上重大进化的转变,对生物的形态、生理、行为和生态均有许多潜在的影响,虽然胎生也会有较多弊端,例如妊娠期母体死亡会导致整胎子代死亡等,但是大多情况下体内受精发育的胎生具有更多的选择优势。鱼类作为数量最多的一类脊椎动物,截至2019年全球已命名的鱼类约为34 200种[1],并进化出多种多样适应性的生殖模式,由最传统最常见的卵生,到部分软骨鱼类中接近陆生哺乳动物的胎生,其中又包括过渡阶段的卵胎生模式、不同的产卵类型及不同形式的亲体抚育行为[2-3]。

随着科学技术的不断发展,越来越多的卵胎生鱼类被发现和研究,但近年来国内外学者缺乏对卵胎生硬骨鱼类的整理和归纳。本文中首先对脊椎动物不同的生殖模式定义进行描述,在此基础上整理和归纳了鱼类的生殖模式分类和定义,对目前已发现的卵胎生硬骨鱼类及其特殊的生殖模式进行了对比分析,梳理了卵胎生硬骨鱼类的进化机制脉络,并对不同类型的卵胎生硬骨鱼类繁殖生理学特性进行了综述,以期为国内外卵胎生鱼类研究提供有益参考。

1 生殖模式概述

1.1 脊椎动物生殖模式分类

繁殖无疑是生物体生命史中最为重要的进程之一,不同的生殖方式代表了亲代在生殖过程中的投资策略,并随着演化产生多样化。根据Lodé[4](2012)的综述,基于合子发育阶段及与亲本相互关系,可将生物生殖模式分为5种:体外受精卵生(Ovuliparity)、体内受精卵生(Oviparity)、卵胎生(Ovoviviparity)、组织营养型胎生(Histortophic viviparity)和母血营养型胎生(Hemotrophic viviparity)。1)体外受精卵生,即为传统意义上的卵生,雌性将卵细胞释放在环境中,与同样释放在环境中的雄性配子(精子)结合并完成受精,这种方式在硬骨鱼类、蟾蜍等两栖动物中较为常见。2)体内受精卵生,不同于传统意义上的卵生,受精过程发生在雌性生殖系统中,并同时产生坚固的卵壳(Eggshell),随后发育中的胚胎经排卵后在体外继续进行孵化。这种方式在鸟类中十分常见,也见于一些两栖和爬行动物,不同于作为恒温动物的鸟类,两栖和爬行动物经常通过筑巢以提供卵孵化温度;同样,这种方式也存在于一些高级硬骨鱼类和软骨鱼类中。3)卵胎生,主要特征是受精卵在体内孵化,但亲体和子代无直接营养交换,即胚胎发育依靠卵黄营养(Lecithotrophy),这其中包括两种形式:第一种为体内受精和体内胚胎发育(主要在卵巢),受精卵也可保留在输卵管中,称为“胚胎保留(Embryo retention)”机制,这在一些鱼类、两栖和爬行动物中可见[5];而另一种为受精作用发生在体外,但受精卵被摄取或储存在体内,例如一些慈鲷科鱼类的口腔孵化,以及海马属Hippocampus鱼类的雄性个体育儿[6-7]。笔者认为这种情况下,胚胎发育在口腔或育儿囊中进行,不是发生在生殖系统中,不应属于体内发育。4)胎生,主要表现为胚胎在母体中发育,但不同的营养途径可将胎生分为两种类型:组织营养型胎生和母血营养型胎生。组织营养型胎生营养来源不仅有卵黄,同时也有母体提供的额外营养(Matrotrophy),一般这种营养供给是通过一些特殊的组织完成,如腺体的分泌,常见于一些双翅目或鳞翅目昆虫,也称为腺营养胎生(Adenotrophic viviparity)。在一些板鳃亚纲鱼类[8]中,输卵管中的胚胎会残食其他卵或胚胎(食卵型,Oophagy)作为营养来源,也归类为组织营养型胎生。5)母血营养型胎生,主要表现为不含卵黄的受精卵通过胎盘等结构源源不断地获取母体血液中的营养,这也是大多数具胎盘哺乳动物的生殖方式。

1.2 鱼类生殖模式分类

鱼类作为物种数量最多的一类脊椎动物,同样存在不同的生殖模式。Balon[8](1981)的综述中按照亲体抚育(Parental care)行为将其分为3大类6小类,即无护幼(Nonguarders)行为、护幼(Guarders)行为和体内孕育(Internal bearers)行为。除体内孕育行为,其余均为体外受精的卵生类型,将体内孕育方式分为4种:1)兼性体内受精型(Facultative internal bearers),正常的卵生鱼类中通过关闭生殖孔通道,偶尔发生的体内受精,受精卵可能在雌性的生殖系统中保留,直至其完成胚胎发育早期阶段;2)专性卵黄营养型(Obligate lecithotrophic livebearers),卵在体内受精,在雌性生殖系统内孵育,直至受精卵发育至破膜的胚胎,以卵黄为营养源;3)母体额外营养食卵型(Matrotrophous oophages and adelphophages),由母体提供胚胎和幼体发育所需营养,主要是其他发育较慢的胚胎或未受精的卵细胞;4)胎生型(Viviparous trophoderms),胚胎发育所需的所有营养和气体交换均由母体提供,具有特定的交换器官(胎盘类似物)。Patzner[3](2008)将其结果整合为卵生(Oviparity)和胎生(Viviparity)两大类:卵生主要是指配子在体外受精和体外发育,即传统意义上的卵生,也存在部分专性卵黄营养卵生和兼性体内受精型卵生(卵胎生);而胎生包括母体额外营养食卵型和胎生,这种现象多出现在软骨鱼中。

结合Balon[8]和Patzner[3]对鱼类生殖模式的分类,以及Lodé[4]对脊椎动物生殖模式的综述,笔者根据鱼类生殖模式以受精及发育场所(体外和体内)、营养类型(专性卵黄营养、兼性卵黄/母体营养和专性母血营养型)和发育程度(胚胎和幼鱼)等特征,对其进行了综合分类:1)体外受精卵生(Ovuliparity),是指大部分硬骨鱼类(包含口腔、育儿囊等非生殖系统孵化的鱼类),营卵黄营养;2)体内受精卵生(Oviparity),受精发生在生殖系统中,受精卵和胚胎在不同发育阶段排出体外[9],营卵黄营养是卵生和卵胎生的过渡;3)卵胎生(Ovo-viviparity),受精卵和胚胎在生殖系统中发育,产出能自由游动的仔鱼,混合卵黄营养和母体渗透营养[10-14];4)胎生(Viviparity),受精卵在母体中发育成自主游动的幼鱼,其所需要营养主要由母体提供,包括特殊结构(胎盘)的营养转运和子宫内同类相食,主要是指软骨鱼类[15]。

2 卵胎生硬骨鱼类地理分布和进化意义

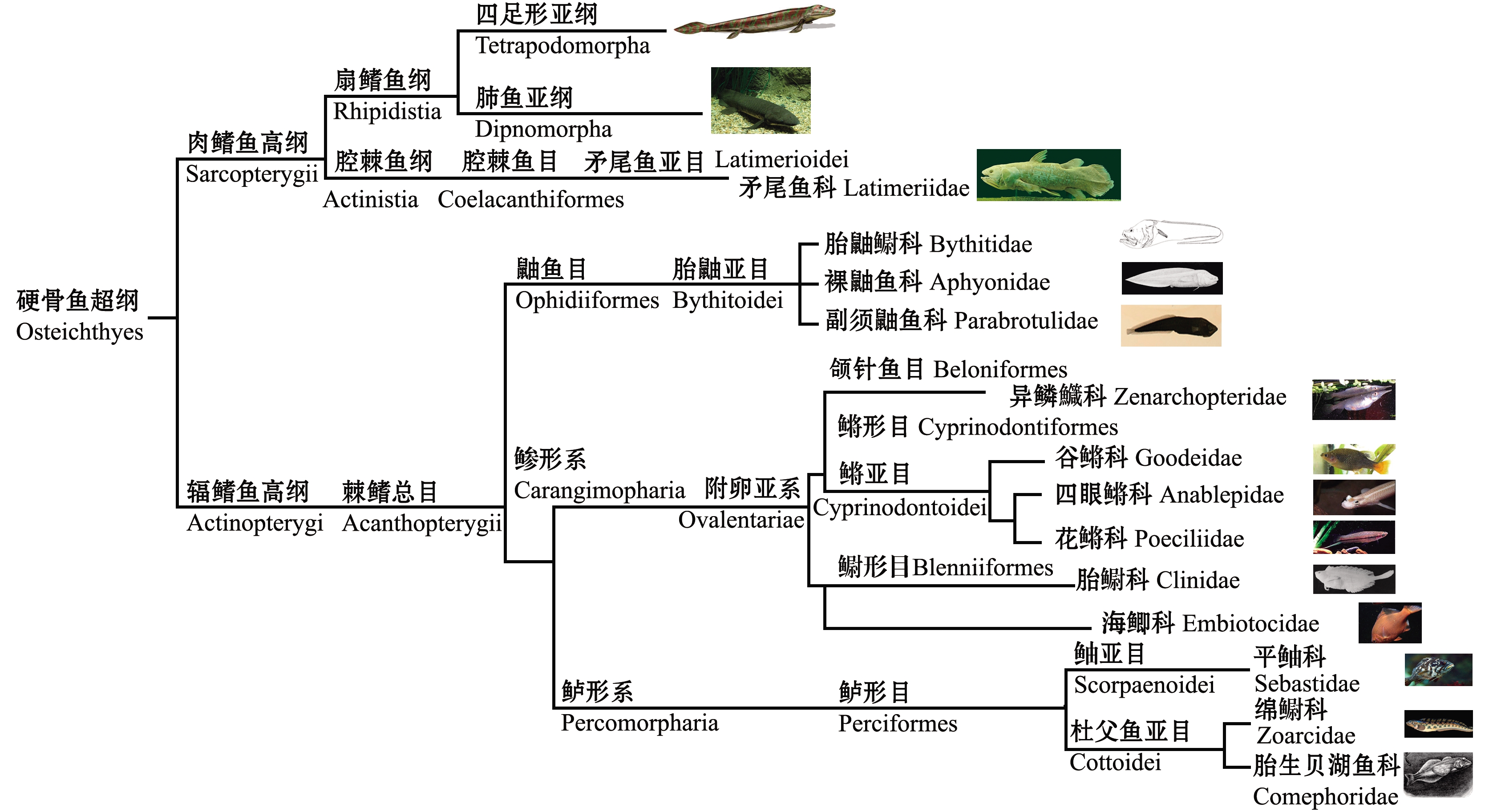

日本学者Koya[16](2008)整理得到3类卵胎生硬骨鱼,即花鳉科Poeciliidae、绵鳚科Zoarcidae和鲉科Scorpaenidae(现为鲈形目Perciformes下鲉亚目Scorpaenoidei[17])。不过经过10余年鱼类繁殖生理学的研究和发展,根据Betancur-R分类系统[17],笔者整理得到7目13科至少132属,约760余种硬骨鱼被归类为卵胎生(表1)。其中矛尾鱼科分类在肉鳍鱼高纲下,而其他卵胎生物种则均为辐鳍鱼高纲下棘鳍总目物种(图1)。

图1 已知卵胎生硬骨鱼分类阶元与进化关系简图[17]

Fig.1 Phylogenetic classification and evolutionary relationship of known ovoviviparous teleost[17]

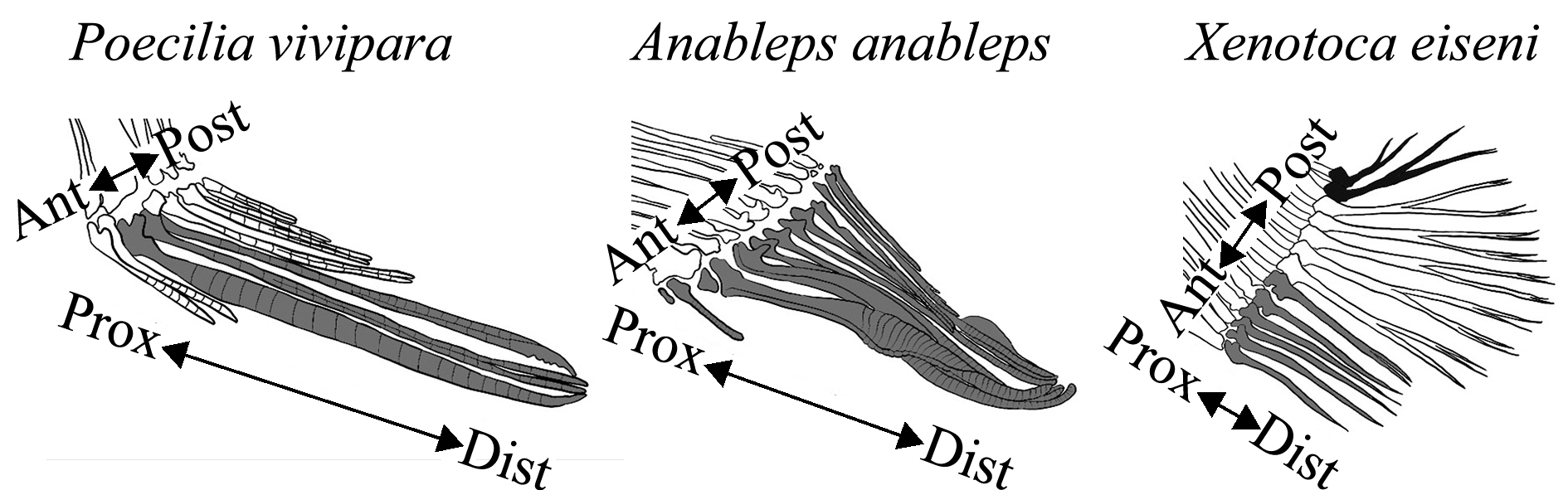

表1 现存已知卵胎生硬骨鱼

Tab.1 Classification of known ovoviviparous teleost

含卵胎生鱼类目order containing ovoviviparity of ichthyosae含卵胎生鱼类科及科下种属数量family or genus containing ovoviviparity of ichthyosae腔棘鱼目Coelacanthiformes;命名者Berg L S, 1937矛尾鱼科Latimeriidae;命名者Smith, 1939;1属2种鼬鱼目Ophidiiformes;命名者Berg L S, 1937胎鼬鳚科Bythitidae;命名者Gill T N, 1861;53个属198个种裸鼬鱼科Aphyonidae;命名者Jordan & Evermann, 1898;7个属29个种副须鼬鱼科Parabrotulidae;命名者Nielsen, 1968;2个属3个种颌针鱼目Beloniformes;命名者Berg L S, 1937异鳞鱵科Zenarchopteridae;命名者Fowler, 1934;5个属59个种鳉形目Cyprinodontiformes;命名者Berg L S, 1940谷鳉科Goodeidae;命名者Jordan & Gilbert 1883;18个属50个种四眼鳉科Anablepidae;命名者Bonaparte, 1831;3个属16个种花鳉科Poeciliidae;命名者Bonaparte, 1831;24个属250个种鳚形目Blenniiformes;命名者Bleeker, 1860胎鳚科Clinidae;命名者Swainson, 1839附卵亚系Ovalentariae;命名者Smith W L and Near T J, 2012海鲫科Embiotocidae;命名者Agassiz, 1853;13个属25个种鲈形目Percifomes;命名者Bleeker, 1863平鲉科Sebastidae;命名者Kaup, 1873;4个属124个种绵鳚科Zoarcidae;命名者Cuvier, 1829;1个属6个种胎生贝湖鱼科Comephoridae;命名者Günther, 1861;1个属2个种

注:数据整理于 Froese R, Pauly D.FishBase, the Global Database of Fishes 2019. https://www.fishbase.de[1]

Note:Data collected from Froese R, Pauly D. FishBase, the Global Database of Fishes 2019. https://www.fishbase.de[1]

2.1 卵胎生物种的地理分布

腔棘鱼目Coelacanthiformes是一类已经几乎灭绝的肉鳍鱼类,其进化地位相比于辐鳍鱼类更接近肺鱼(Lungfish)和四足动物(Tetrapods),后者更是现代两栖动物、爬行动物和哺乳动物的共同祖先。腔棘鱼均为体内受精的卵胎生鱼类[18],目前仅存矛尾鱼科Latimeriidae下的2个种:分布于非洲东部西印度洋海岸的西印度洋矛尾鱼Latimeria chalumnae[19]和分布于印度尼西亚岛屿周边的印尼矛尾鱼Latimeria menadoensis[20],目前被认为是腔棘鱼类的“活化石”。

棘鳍总目Acanthopterygii下有3个主要的卵胎生分支,分别为:1)进化相对落后的鼬鱼目Ophidiiformes;2)附卵亚系Ovalentariae下的鳉形目Cyprinodontiformes、颌针鱼目Beloniformes、鳚形目Blenniiformes和海鲫科Embiotocidae;3)进化较为高级的鲈形目Percifomes下的鲉亚目Scorpaenoidei和杜父鱼亚目Cottoidei。

(1)鳉形目为一类外形各异的小型热带淡水鱼,其中卵胎生物种包括花鳉总科Poecilioidea下的四眼鳉科Anablepidae和花鳉科Poeciliidae,以及底鳉总科Fundulidae下的谷鳉科Goodeidae,自然种均主要分布于美国和墨西哥南部[21]。花鳉科下的3个亚科中,仅有美洲种花鳉科为卵胎生类型。此结果表明,这些亚科间的差异可能与1亿年前非洲大陆和美洲大陆的分裂有关,在南美洲大陆进化出卵胎生生殖模式之后迁移至中美洲。谷鳉科卵胎生的特殊性可以归因于该地区的历史火山和地质扰动,为鱼类的异源物种形成创造了合适的条件[22]。

(2)颌针鱼目下异鳞鱵科Zenarchopteridae有3个卵胎生属,分别为皮颏鱵属Dermogenys、齿鱵属Hemirhamphodon和正鱵属Nomorhamphus,分布于东南亚地区的淡水水域[23]。

(3)海鲫科目前在附卵亚系中未确定分类地位[24],其虽然与鳉形目和颌针鱼目同属一个分类群,但体型形态和生境差异较大,海鲫科鱼类主要分布在太平洋东北部的中纬度地区,环境水温较低,体型较大(平均个体长约20 cm,最大个体为47 cm),每批产仔数也较多。

(4)鳚形目Blenniiformes下的胎鳚科Clinidae类群,有超过16个物种属于卵胎生,包括钝吻草鳚Clinus cottoides、鼠胎鳚Fucomimus mus等,广泛分布在西太平洋和非洲南部,大部分体型较小[25]。

(5)鲈形目下有两个亚目,即鲉亚目和杜父鱼亚目含有卵胎生物种,分别为鲉亚目的平鲉科Sebastidae,以及杜父鱼亚目的绵鳚科Zoarcidae和胎生贝湖鱼科Comephoridae[17]。平鲉科下的眶棘鲉属Hozukius、无鳔鲉属Helicolenus、平鲉属Sebastes、菖鲉属Sebastiscus为分布在北太平洋和北大西洋的深水鱼类,体型较热带鱼大,每批产仔数较多,其中,许氏平鲉Sebastes schlegelii、褐菖鲉Sebastiscus marmoratus等许多物种均为常见的经济物种。绵鳚科下仅有绵鳚属Zoarces中6个物种为卵胎生,分布在大西洋西北部和大西洋东北部的中高纬度沿海地区。胎生贝湖鱼科下仅有的两个种——小眼胎生贝湖鱼Comephorus baikalensis和胎生贝湖鱼Comephorus dybowskii是近几年报道较多的卵胎生物种,仅分布在俄罗斯贝加尔湖中,属于低温深水卵胎生,每批产仔数较多[26]。可以看出,鲈形目下的这3个卵胎生科和海鲫科都分布在太平洋和大西洋中高纬度地区,环境水温较低,且每批产仔数也较多。

(6)鼬鱼目下有3个卵胎生类群,分别为胎鼬鳚科Bythitidae、裸鼬鱼科Aphyonidae和副须鼬鱼科Parabrotulidae,虽然胎鼬鳚科和裸鼬鱼科分布在热带和亚热带,但它们却是深海物种,副须鼬鱼科同样也是分布在高纬度地区的温冷水物种[27]。

2.2 卵胎生物种的进化意义

总的来看,除肉鳍鱼分支下的矛尾鱼科外,目前已确定的卵胎生硬骨鱼按生境可大致划分为低纬度热带淡水的鳉形目、颌针鱼目和胎鳚科,以及高纬度中低温的鼬鱼目和鲈形目部分物种。有学者在爬行动物生殖策略进化的研究中提出了“冷气候假说(Cold-climate hypothesis)”,即低温环境下进化出卵生/卵胎生是为了维持胚胎发育的环境稳定[28],如对角蜥科Phrynosomatidae物种的研究中发现,较低的温度和胎生现象的相关性更大,这可能与产卵和孵化季节的温度变化更有利于倾向胎生的选择性压力有关。然而,该研究同样发现,胎生的进化频率似乎在热带出现的更频繁[29]。在对热带卵胎生/卵生爬行动物的选择适应研究中发现,繁殖期雌性选择体内胚胎发育控制适宜温度来保证后代健康水平的最大化,即“母体操作假说(Maternal manipulation hypothesis)”[30]。同样也有研究发现,部分软骨鱼类会通过选择水温较高的环境提高自身体温以增加摄食效率和缩短妊娠时间,甚至会通过聚集的方式增加体温[31-32]。这些研究一定程度上也能解释硬骨鱼类生殖模式进化的现象:中高纬度的低水温物种,表现为较大的个体以及介于热带卵胎生鱼和卵生鱼的单次怀仔量,导致这些物种面临着低温环境和提高子代成活率的选择压力,从而进化出卵胎生机制。例如,绵鳚Zoarces viviparus妊娠期一般能持续约5个月,分娩一般出现在水温最低的时候[33-34]。而分布在热带和亚热带的小型鱼类,卵胎生机制是个体在体内受精以提高受精率、集中生殖能量给少数受精卵,以及高效利用外界高温进一步提高生殖成功率的权衡,也符合“母体操作假说”。从进化和物种迁移的角度看,花鳉科在南美洲大陆和非洲大陆分开之前就已经存在,但在地理种群分开后,南美洲的花鳉科种群才进化出卵胎生机制,然后进一步迁移到中美洲地区[35]。目前可以假设这两种起点不同但殊途同归的卵胎生进化机制,但仍缺少对这两种基于环境选择的卵胎生进化方向的内在机制的研究。

3 卵胎生硬骨鱼类的繁殖生理学

鱼类生殖模式表现出丰富的多样性,但卵胎生生殖模式下也会有较大的差异。例如,无论是热带还是冷温带,这些地区的卵胎生硬骨鱼的配子成熟和性腺发育模式相同,但是时间上差异明显,而且受精受孕的方式也不尽相同;同为鳉形目下的花鳉科、四眼鳉科和谷鳉科分别进化出各异的交配器官;不同的鱼类也有不同的精子储存系统。在此笔者以热带淡水花鳉科等鱼类和中冷温海水中的平鲉科等鱼类为主要对象,主要介绍其卵胎生生殖模式下性腺成熟和配子发生、交配器官发育、交配行为、精子储存、妊娠维持等繁殖生理学事件。

3.1 配子发生和性腺成熟

相对于雄性更高的精子产量,雌性卵母细胞的数量和质量决定了胚胎发育所需的绝大多数营养物质合成和储存,因此,近年来对卵胎生鱼类生殖生物学的研究倾向于雌性[36]。绝大多数卵胎生鱼类性腺发育阶段和配子成熟与卵生鱼无太大差异。卵子发生会经过Ⅰ期卵母细胞、Ⅱ期卵母细胞和后续的卵黄发生阶段,随着减数分裂开始,卵细胞成熟。唯一不同的是卵胎生鱼类存在卵母细胞受精后阶段,即卵巢发育中的妊娠期[37-38],不过由于硬骨鱼穆勒氏管尚未发育,受精卵和胚胎发育场所仍在卵巢而不是输卵管[39]。精子发生同样与卵生鱼无异,即在生精上皮完成精原细胞到精母细胞分化,随后形成精子细胞,并变形拉长,产生成熟精子。与卵生鱼不同,卵胎生生殖方式下的受精发生在体内,导致部分卵胎生鱼类成熟精子排出体外的形式为精子囊或精子束而不是游离精子[37, 40]。

目前,鳉形目已发现约有300种卵胎生鱼类,其中,大多数花鳉科卵胎生鱼类中雌雄比例偏向雌性,这可能是因为雌性体型较大、寿命更长,同时雄性由于鲜艳的体色更容易受到掠食者捕食,并且较小的体型导致对进化压力更为敏感,雄性死亡率较高[41]。但也有学者认为,温度对性别比也有较大影响,如孔雀鱼雄性比例随着温度升高而升高[42-43]。花鳉科鱼类因其热带生存环境,雌性卵黄发生、卵母细胞成熟、受精和分娩约在1个月内完成。在这个类群中,有些物种的胚胎发育具有多个阶段,如异小鳉属Heterandria中存在异期复孕现象,食蚊鱼Gambusia affinis在一个较长的生殖季节中也会出现在短时间内可以重复分娩、多产仔的现象[44]。对鳉形目卵胎生鱼类的研究发现,其性腺成熟和分娩间隔受温度和光周期的共同影响[45-46],其中,温度主要影响性腺和胚胎发育速率,光周期主要影响卵黄生成速率。食蚊鱼出生时发生性别分化,出生几天后,成对的卵巢融合成单个的被卵巢;雄性大约在出生90 d后开始性腺成熟,雌性在出生110 d后性腺成熟,即在雌性生殖过程中,卵黄生成期卵母细胞首次出现在出生后90 d,并在出生后110 d达到成熟前期[47]。而谷鳉科鱼类首次性腺成熟时间在7—8个月内,两次分娩时间间隔平均为45 d[48]。与鳉形目鱼类相似存在异期复孕现象。鼠胎鳚在一年内的大多数月份均保持生殖活性,雄性精巢中长期可以观察到精子,雌性生殖季节主要集中在5月至次年2月[49]。虽然异鳞鱵科和鳉形目下的卵胎生鱼类均属于热带种,但不同的是异鳞鱵科的某些物种中缺少异期复孕现象(如正鱵属、皮颏鱵属),且同时存在专性卵黄营养的卵胎生形式(如齿鱵属、正鱵属和皮颏鱵属下一些物种)和兼性母体渗透营养形式[50]。

鲈形目下两个较为典型的卵胎生鱼类分别为平鲉科和绵鳚科,这两个科下的卵胎生鱼类均属于北方中冷温带海水鱼。绵鳚科下的绵鳚是较早确定的卵胎生物种,因为该鱼也生活在相对被污染的环境中,近年来常被作为指示内分泌干扰物质影响的指示生物[34]。以长绵鳚Zoarces elongatus为例,概括绵鳚科详细的卵巢组织学周年变化[51]:长绵鳚的卵黄发生在5—8月,9月卵巢腔中卵母细胞成熟、排卵并受精,10月卵巢内的受精卵孵化,孵化后的胚胎在卵巢内继续生长,在3—4月分娩。推测雌雄的交尾发生在8月左右,因为精巢的发育刚好在排卵之前,但卵巢内未发现特化的贮存精子的结构[51-52]。绵鳚和长绵鳚的生殖周期几乎相同,通常在5月或6月性腺开始发育,8月成熟卵母细胞排出并受精,受精卵在卵巢腔内发育到12月,次年1—2月出生[33]。平鲉科下平鲉属中有108个卵胎生物种,约占平鲉科4/5。平鲉属生殖周期以边尾平鲉Sebastes taczanowskii和许氏平鲉为例:雄鱼功能性成熟和交配一般发生在11月(具体时间取决于季节和水温),此时雌鱼开始卵黄生成作用,次年3—4月卵黄生成作用完成,卵母细胞成熟并完成排卵,一般认为,受精发生在卵母细胞成熟后的卵巢中,并在5月分娩[53],分娩前胚胎在卵巢中孵化,幼鱼一次性通过泄殖孔排出[54]。妊娠期间胚胎通过吸收卵黄营养和母体血液渗透营养进行发育[55-57],卵巢或胚胎并无特殊的营养器官[58]。分娩时间依不同种的生态栖息地有所不同[59-60],在妊娠期间下一轮发育的卵母细胞并不启动卵黄生成作用[60]。在对许氏平鲉性腺发育和成熟的研究中,学者们深入探索了多种参与性腺成熟的基因和类固醇激素合成相关酶基因,包括参与前期性腺分化的vasa和成熟后性腺发育的foxl2[61-62],参与配子成熟的促卵泡激素(fsh)和促黄体激素(lh)受体fshr和lhr[63],以及雌激素受体erα和erβ[64-65]。在性腺成熟的不同阶段,这些功能基因表达谱展现出与形态学观察到的性腺发育同步。

海鲫科作为附卵亚系下未分类的科,其体型和生殖力也介于鲈形目和鳉形目间,且科内生活史差异较大,体型较大的物种具有较高的生殖力和寿命,体型较小的物种生殖力较低且寿命较短[66]。加利福尼亚南部海鲫Embiotoca jacksoni的交配行为发生在7—11月,妊娠期为12月至次年5月[67],且在多个物种中观察到了多父权现象,这与海鲫科中进化出复杂的卵胎生机制相关[68]。

3.2 交配器官发育

为成功完成体内受精,胎生或卵胎生雄性会进化出特别的生殖器以将雄性配子传递到雌性体内,一般表现为生殖道的体外增生形式[69-70]。而对于卵胎生硬骨鱼,以鳉形目卵胎生鱼类臀鳍形成的特殊交配器官称为生殖肢(Gonopodium)[71],以平鲉属卵胎生鱼类在生殖季节产生的肉质性的尿殖突(Urinogenital papillae)[72-73]为主要形式。

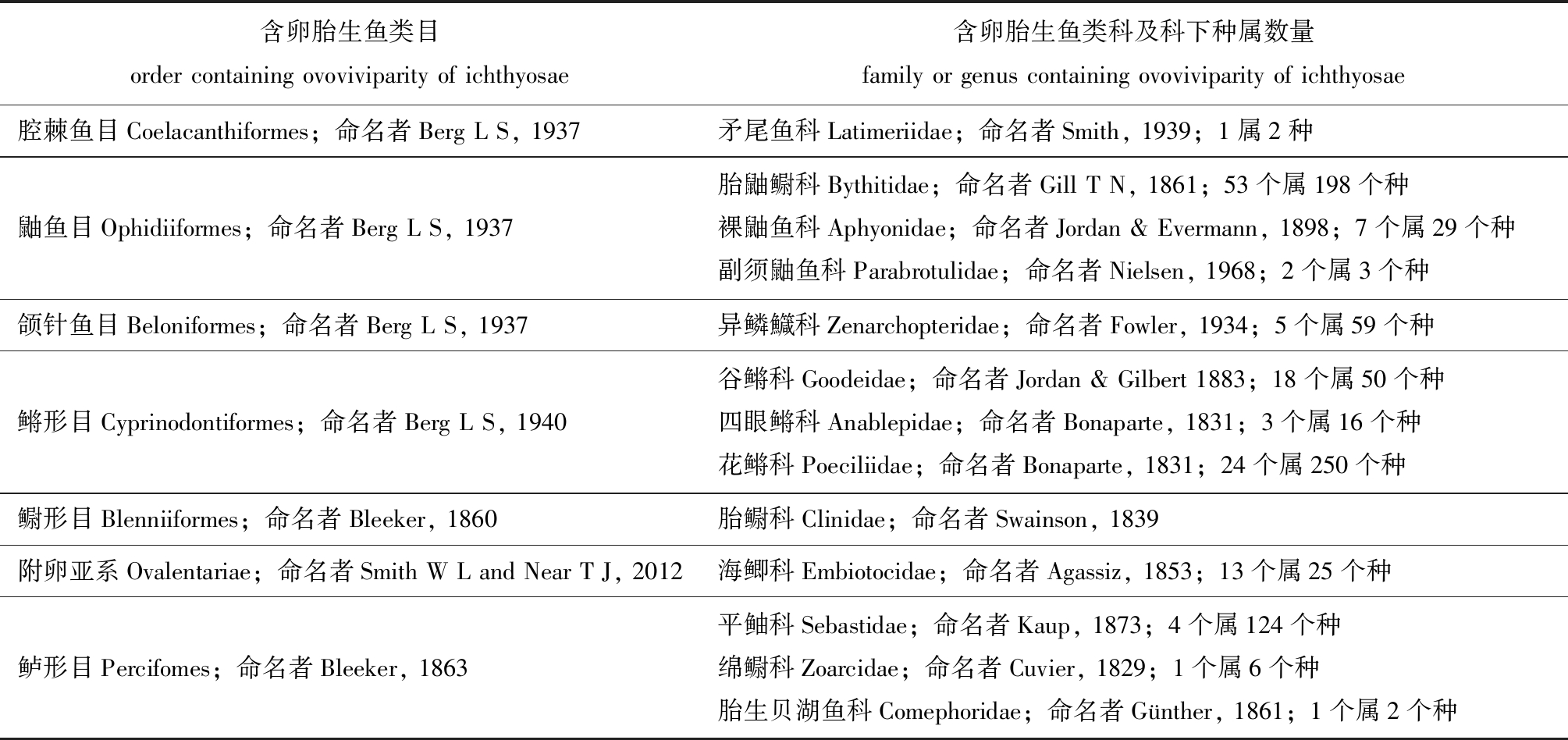

在花鳉科中,雄性臀鳍产生一个由臀鳍第三、第四和第五个鳍条延长特化为钩状结构,尾部与脊椎相连[74-75],其形成受雄性激素影响[75],且在交配季节伸入雌性尿殖窦中传递精子(图2)。四眼鳉科臀鳍完全扭曲特化产生的交配器官呈不对称形态,产生向左或向右扭曲的生殖肢[76],雌性生殖孔同样为类似向左或向右的形态,这就导致这种鱼类的交配行为必须按照其交配器官的方向偏好进行,即左边偏向的雄性只能与右边偏向的雌性交配[77],这种不对称的设计可能在交配中更灵巧。谷鳉科鱼类臀鳍前6个鳍条和后面的鳍条分裂开,形成一个短的生殖肢,且雄性生殖肢也存在类似于四眼鳉科的左右不对称性,不过雌性并无这种生殖器的不对称性[78],可以接受两种扭曲方向的雄鱼[79]。

在平鲉科中,对黑腹无鳔鲉Helicolenus dactylopterus[9]、褐菖鲉[72]、许氏平鲉[73]的肉质性尿殖突研究较多,这3种平鲉科的卵胎生鱼类,在幼年时期不具有尿殖突,性成熟后雄鱼会生长出尿殖突,并在交配季节充血并有所延长。相比于花鳉科特化的生殖肢,这种肉质性尿殖突相对原始,结缔组织构成的突出结构在非生殖季节参与泌尿系统活动,在生殖季节向前突出膨胀可插入雌性生殖道中传递精子[80](图3)。

南非周边的胎鳚科下物种虽然属于南半球中温带,但体型较热带花鳉科鱼类大,且交配器官也属于肛门后开口的肉质尿殖突。不同于冷温环境下的平鲉科物种,胎鳚科物种在腹腔内存在一个壶腹状结构,该结构外层包裹大量肌肉,内层包含大量精子,体外的肉质尿殖突则为该壶腹结构的体外延伸[25, 49]。

注:灰色鳍条为臀鳍特化的生殖肢;黑色鳍条为艾氏异仔鳉侧边扭曲的臀鳍;Ant为前部;Post为后部; Prox为近端;Dist为远端

Note:Gray shading indicates the formation of gonopodia from anal fin rays in each species;Black shading shows lateral-turning anal fin rays in Xenotoca eiseni; Ant, anterior; Post, posterior; Prox, proximal; Dist, distal

图2 鳉形目下胎花鳉、四眼鳉和艾氏异仔鳉臀鳍生殖肢结构图

Fig.2 Anal fin structures of ovoviviparity species Poecilia vivipara, Anableps anableps and Xenotoca eiseni belonging to order Cyprinodontiformes

3.3 精子储存

在生物界中,部分动物交配后雌性会将精子储存在体内,这在进化中意义重大:在时间上将交配与受孕分开,精子储存可以适应生态多样化的栖息地、影响生活史、交配系统、配偶选择、精子竞争;精子储存可以导致雌性和/或雄性迥异的进化压力,有时产生协同进化;精子储存可以延长精子生成、交配与受精之间的窗口期,增加交配后性选择机会[81]。在鱼类中,精子储存现象同样十分常见,且不局限于卵胎生和胎生鱼类[82-85]。

对于体内受精的卵胎生鱼类而言,精子储存的意义同样不可忽视。鳉形目下的卵胎生鱼类精子一般以精子囊的形式进入母体卵巢中,以活性形式储存在卵巢中并与滤泡中成熟卵母细胞完成受精作用[86]。对月光鱼Xiphophorus maculatus卵巢的透射电镜研究发现,月光鱼交配后可在输卵管上皮观察到精子头埋在上皮皱褶处,并可观察到精子包裹在输卵管上皮中的一类精子相关细胞中(Sperm-Associated Cells,SAC),这类SAC细胞间独特的桥粒结构形成的屏障也在一定程度上解释了外源精子为何能避开母体免疫反应长期储存在卵巢中,这在其他存在卵巢精子储存的物种中也有报道[83]。这种精子以精子囊或精子束的形式将头部埋在卵巢上皮组织,尾部游离在卵巢腔中的现象,在花鳉科鱼类中也较为常见(如墨西哥食蚊鱼Gambusia panuco、剑尾鱼Xiphophorus hellerii、短鳍花鳉Poecilia mexicana、多育若花鳉Poeciliopsis prolifica、哑若花鳉Poecilioposis infans、壮体若花鳉Poeciliopsis viriosa、中美洲若花鳉Poeciliopsis presidionis、若花鳉Poeciliopsis gracilis和美丽异小鳉Heterandria formosa),且将这种卵巢腔上皮内凹形成的储存精子的袋装结构称作凹痕“dellen”。无论是以成团还是以分散的形式存在,这种在花鳉科中有方向性的精子储存方式可能与保持精子活性有关。异期复孕的花鳉科鱼类卵巢中存储的精子量多于无异期复孕的花鳉科鱼类[87]。早期有文献指出,雌性谷鳉卵巢不储存精子,不过随着研究技术进步,该结果需要进一步证实[88]。胎鳚科下的鼠胎鳚也存在相似的口袋结构储存精子,且这个口袋结构周围的细胞也比卵巢基质细胞更大[49]。

注:A、B分别为雄雌许氏平鲉生殖孔外观照片;A′、B′分别为雄雌许氏平鲉生殖孔Masson染色切片;A″、B″分别为雄雌许氏平鲉生殖孔模式图;C为黄鳍鳝胎鳚生殖孔扫描电镜结构;D为鼠胎鳚生殖孔结构图;a为壶腹;io为插入器官;t为精巢;ub为膀胱;k为肾脏

Note: A and B, appearance of the urinogenital papillae of male and female jacopever Sebastes schlegelii; A′ and B′, masson trichrome staining of urinogenital papillae of male and female jacopever Sebastes schlegelii; A″ and B″, schemas of the urinogenital papillae of male and female jacopever Sebastes schlegelii; C, the reproductive organs of nosestripe klipfish Muraenoclinus dorsalis (SEM); D, schema of the urinogenital papillae of mousey klipfish Fucomimus mus; a, ampulla; io, intromittent organ; t, testes; ub, urinary bladder; k, kidney

图3 平鲉科下雌雄许氏平鲉及胎鳚科下黄鳍鳝胎鳚[25]和鼠胎鳚[49]的生殖孔结构图

Fig.3 Structure of urinogenital papillae of jacopever Sebastes schlegelii in Scorpaenidae, and nosestripe klipfish Muraenoclinus dorsalis[25] and mousey klipfish Fucomimus mus in Clinidae[49]

在储存精子的卵胎生黑腹无鳔鲉中,同样可以观察到精子按一定方向储存在卵巢腔上皮的特定结构中,这种结构称为“隐窝”,且在精子储存阶段隐窝周围富含大量毛细血管,可能与维持精子活性有关,同时隐窝会分泌大量多糖和蛋白并显示酸性黏多糖阳性,可能与酸性下精子活力被抑制有关,黑腹无鳔鲉的精子储存可长达10个月[9, 89]。在对许氏平鲉的研究发现,11月和12月在卵巢液中发现了精子,但对应月份的组织切片中却找不到精子,在次年1—3月,卵巢腔中无法发现精子的存在,但从组织学切片上观察到精子穿透包裹滤泡层的产卵板(Ovigerous lamellae)上皮中,这表明精子在储存初期可能在卵巢液中自由漂浮[60]。稀棘平鲉Sebastes paucispinis和边尾平鲉精子同样储存在包裹滤泡的产卵板上皮细胞中[53, 90],但交配后不同阶段的精子储存位置同样存在差异。有报道指出,海鲫科的墨西哥海鱼与Cymatogaster aggregata也存在长达5个月的精子储存现象,这与父权选择和确保受精成功相关,但并未见精子储存组织学相关研究[91-92]。这些卵胎生鱼类的精子储存现象的重要性体现在:通过控制与雄性个体交配时间来主导生殖需求和食物选择,通过淘汰精子进而选择优良性状的雄性配子,最终通过控制排卵和妊娠时机、减少受精时产生的消耗,以保证生殖过程完成。

3.4 妊娠维持和分娩的内分泌机制

卵胎生鱼类的妊娠维持和分娩调控研究始于20世纪60年代,主要参与的类固醇激素为17α,20β-双羟孕酮(DHP,17α,20β-Dihydroxyprogesterone)。在边尾平鲉和许氏平鲉中随着卵母细胞成熟DHP水平迅速上升,并在妊娠期间维持较高浓度,分娩前后迅速下降[60, 93]。纵痕平鲉的血浆C21类固醇浓度在妊娠期上升,在分娩后迅速下降。然而在该物种中,17α,20β-DHP-5β的增加速率要高于DHP[59]。即使合成速率不同,平鲉属C21类固醇在卵母细胞成熟到妊娠期间均有一定作用。不过也有学者认为,孕激素在平鲉科鱼类妊娠期间未有显著变化,推测无特别功能,可能仅和其他卵生鱼一样参与卵母细胞的最后成熟[93-94]。同样的现象在孔雀鱼中也能观察到。孔雀鱼中卵黄发生后雌激素的合成迅速下降,而DHP开始生成,且在卵母细胞发育和妊娠期间无变化,仅在受精期间浓度较妊娠期高[95-96]。但包括DHP在内的孕激素在整个分娩期未显著变化,说明类似于平鲉科一样DHP可能并不参与维持妊娠[95, 97]。

分娩的内分泌调控实验始于20世纪60年代,通过激素注射法,Venkatesh和其团队在20世纪80年代至90年代解决了大多数关于花鳉科鱼类的分娩调控机制。花鳉科鱼类的成熟胚胎从滤泡中排出类似于卵生硬骨鱼的排卵,所以阐述排卵的机制就显得十分有必要。诸多研究表明,鱼类排卵和前列腺素(Prostaglandins, PGs)密切相关。体外注射前列腺素F(PGF)可以显著提高细鳞肥脂鲤Piaractus mesopotamicus的排卵率,同时不影响其孵化率[98]。抑制环氧化酶(Cyclooxygenase,COX,前列腺素合成关键酶)或拮抗前列腺素E2受体会影响青鳉Oryzias latipes排卵[99]。对孔雀鱼分娩后滤泡组织进行分析发现,该组织可以花生四烯酸为前体合成前列腺素[100],且这种合成仅在妊娠中后期上升[101]。对妊娠期孔雀鱼进行PGE2或PGF2α注射可引起分娩和早产[102]。cAMP、foskolin和皮质醇可抑制孔雀鱼卵巢合成前列腺素[100-101],这与妊娠期血液皮质醇水平较高、分娩前迅速下降相一致[101]。花鳉科鱼在分娩时,卵巢分泌的前列腺素可能首先使滤泡分解,分离胚胎,然后通过神经垂体激素分泌诱导平滑肌收缩促进胚胎从卵巢中分离,其生理机制还有待于进一步研究。

4 存在问题与展望

本文中归纳出了4个鱼类常见的生殖模式:体外受精的卵生、体内受精的卵生、卵胎生和胎生,并且对其中最为特殊的卵胎生硬骨鱼类进行了综述。从地理分布角度看,这些现存已知的卵胎生硬骨鱼主要分布在低纬度热带地区,包括美洲和东南亚地区,以及高纬度地区的温冷水环境。这种由于地理分布导致的生殖模式演化机制,比较接近爬行动物生殖模式研究提出的“冷气候假说”和“母体操作假说”。针对卵胎生硬骨鱼类生殖进程的一些重要节点,对包括配子形成和性腺发育、交配器官分化、精子储存和妊娠维持进行分析和比较,以期为鱼类生理研究提供参考和借鉴。

4.1 存在问题与解决途径

(1)鱼类作为数量繁多的一类脊椎动物,由于其多种多样的繁殖模式和繁殖特性,过去对其生殖模式的定义也相对模糊,特别是对卵胎生鱼类的研究几乎仅限制在胎生鲨鱼和淡水鳉形目中。近十多年来,越来越多的研究者将目光聚焦在经济性卵胎生硬骨鱼类领域,例如平鲉科鱼类等。但是鉴于研究领域相对比较狭小,对知识分享和交流造成了一定的障碍。建议将许氏平鲉列为海洋卵胎生硬骨鱼类代表,深入探索其群体遗传学、生理学、生态学、种群地理分布等特征,为揭示硬骨鱼类乃至脊椎动物进化机制提供丰富实验材料。

(2)对于常见性腺同步成熟的卵生鱼类,其交配引发的内分泌机制主要涉及引起排卵和产卵的前列腺素作为性外激素引起雌雄吸引[103],但作为非同步性腺成熟卵胎生硬骨鱼类,这其中的机制是什么,以及这些精子是否来自同一个父本的问题并没有得到解释,目前研究发现,卵胎生鱼类比较普遍存在多重父权选择现象,这种机制在一定程度上维持了物种的遗传多样性[104-106]。建议进一步加强对多父权选择机制的深入研究,这对于揭示卵胎生鱼类进化脉络具有十分重要意义。

(3)对于目前卵胎生鱼类的研究,仍缺少一个标准的卵胎生鱼类模式生物,以及广泛适用于卵胎生鱼类的基因编辑技术。孔雀鱼作为国内最容易获得的卵胎生小型鱼类,其具有容易培养、生长成熟迅速、易于区分雌雄、基因背景清晰等优点。建议使用孔雀鱼作为卵胎生鱼类研究的模式生物,为研究大型海洋经济卵胎生鱼类提供体外表达系统,深入解析生理与进化适应机制。

4.2 展望

尽管目前对卵胎生硬骨鱼类的研究已取得了一定进展,今后仍需在以下几个方面开展研究。

(1)卵胎生硬骨鱼类妊娠维持机制有待进一步研究。在花鳉科鱼中,妊娠和排卵抑制发生在卵泡中,孕酮包括DHP的合成和血浆水平在妊娠期间迅速下降,被认为参与了最终卵母细胞成熟。然而在平鲉科中,妊娠发生在排卵后的卵巢腔中并且抑制卵细胞释放,DHP的合成和血浆浓度在妊娠期间保持较高的水平。因此,认为几种卵胎生硬骨鱼类妊娠维持的机制可能不同。

(2)妊娠期间营养供给机制有待进一步研究。妊娠期间从母体到胚胎的营养供给水平在每个科之间是不同的,胚胎对母体营养的依赖性顺序为平鲉科<花鳉科<绵鳚科。随着胚胎对母体营养依赖程度的增加,各种激素必须参与调节变化,促性腺激素(GtH)可能作为一种调节因子参与类固醇的合成,其作用机制需要深入研究。

(3)卵胎生硬骨鱼类分娩机制有待进一步研究。目前研究表明,无论是哪类卵胎生硬骨鱼类,分娩都与PGs的合成存在密切关系,但具体是哪种PG,其作用机制如何,均需要进一步研究。

致谢: 吕里康和王孝杰博士研究生参与了本文的写作与修改!

[1] Froese R,Pauly D.FishBase,the global database of fishes 2019[EB/OL].(2020-02-01)https://www.fishbase.de/.

[2] Sargent R C,Taylor P D,Gross M R.Parental care and the evolution of egg size in fishes[J].The American Naturalist,1987,129(1):32-46.

[3] Patzner R A.Reproductive Strategies of Fish[M].Fish Reproduction:CRC Press,2008:325-364.

[4] Lodé T.Oviparity or viviparity?That is the question[J].Reproductive Biology,2012,12(3):259-264.

[5] Wake M H.Fetal adaptations for viviparity in amphibians[J].Journal of Morphology,2015,276(8):941-960.

[6] Stelkens R B,Young K A,Seehausen O.The accumulation of reproductive incompatibilities in African cichlid fish[J].Evolution:International Journal of Organic Evolution,2010,64(3):617-633.

[7] Mai A C G,Velasco G.Population dynamics and reproduction of wild longsnout seahorse Hippocampus reidi[J].Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom,2012,92(2):421-427.

[8] Balon E K.Additions and amendments to the classification of reproductive styles in fishes[J].Environmental Biology of Fishes,1981,6(3-4):377-389.

[9] Mu oz M,Koya Y,Casadevall M.Histochemical analysis of sperm storage in Helicolenus dactylopterus dactylopterus (Teleostei:Scorpaenidae)[J].Journal of Experimental Zoology,2002,292(2):156-164.

oz M,Koya Y,Casadevall M.Histochemical analysis of sperm storage in Helicolenus dactylopterus dactylopterus (Teleostei:Scorpaenidae)[J].Journal of Experimental Zoology,2002,292(2):156-164.

[10] 史丹,温海深,杨艳平.许氏平鲉卵巢发育的周年变化研究[J].中国海洋大学学报,2011,41(9):25-30.

[11] 蔺玉珍,于道德,温海深,等.卵胎生许氏平鲉仔鱼与稚鱼发育形态学特征观察[J].海洋湖沼通报,2014(2):51-58.

[12] 赵吉,冯启超,温海深.卵胎生许氏平鲉胚胎离体培养及发育形态学[J].水产学报,2016,40(8):1195-1202.

[13] Kunz Y W,Ennis S,Wise C.Ontogeny of the photoreceptors in the embryonic retina of the viviparous guppy,Poecilia reticulata P.(Teleostei)[J].Cell and Tissue Research,1983,230(3):469-486.

[14] Schindler J F,Hamlett W C.Maternal-embryonic relations in viviparous teleosts[J].Journal of Experimental Zoology,1993,266(5):378-393.

[15] Hamlett W C,Hysell M K.Uterine specializations in elasmobranchs[J].The Journal of Experimental Zoology,1998,282(4-5):438-459.

[16] Koya Y.Reproductive Physiology in Viviparous Teleosts[M]//Rocha M J,Arukwe A,Kapoor B G.Fish Reproduction.Enfield N H:Science Publishers,2008:245-275.

[17] Betancur-R R,Wiley E O,Arratia G,et al.Phylogenetic classification of bony fishes[J].BMC Evolutionary Biology,2017,17:162.

[18] Smith C L,Rand C S,Schaeffer B,et al.Latimeria,the living coelacanth,is ovoviviparous[J].Science,1975,190(4219):1105-1106.

[19] Fricke H,Hissmann K,Schauer J,et al.Habitat and population size of the coelacanth Latimeria chalumnae at Grand Comoro[J].Environmental Biology of Fishes,1991,32(1):287-300.

[20] Danke J,Miyake T,Powers T,et al.Genome resource for the Indonesian coelacanth,Latimeria menadoensis[J].Journal of Experimental Zoology Part A:Comparative Experimental Biology,2004,301A(3):228-234.

[21] Van Der Laan R,Eschmeyer W N,Fricke R.Family-group names of recent fishes[J].Zootaxa,2014,3882(1):1-230.

[22] Webb S A,Graves J A,Macias-Garcia C,et al.Molecular phylogeny of the livebearing Goodeidae (Cyprinodontiformes)[J].Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution,2004,30(3):527-544.

[23] Meisner A D,Burns J R.Viviparity in the halfbeak genera Dermogenys and Nomorhamphus (Teleostei:Hemiramphidae)[J].Journal of Morphology,1997,234(3):295-317.

[24] Nelson J S,Grande T C,Wilson M V H.Fishes of the World[M].New Jersey:John Wiley & Sons,2016.

[25] Fishelson L,Gon O,Holdengreber V,et al.Comparative morphology and cytology of the male sperm-transmission organs in viviparous species of clinid fishes (Clinidae:Teleostei,Perciformes)[J].Journal of Morphology,2006,267(12):1406-1414.

[26] Kozlova T A,Khotimchenko S V.Lipids and fatty acids of two pelagic cottoid fishes (Comephorus spp.) endemic to Lake Baikal[J].Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part B:Biochemistry and Molecular Biology,2000,126(4):477-485.

[27] Møller P R,Knudsen S W,Schwarzhans W,et al.A new classification of viviparous brotulas (Bythitidae)-with family status for Dinematichthyidae-based on molecular,morphological and fossil data[J].Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution,2016,100:391-408.

[28] Shine R.Reptilian viviparity in cold climates:testing the assumptions of an evolutionary hypothesis[J].Oecologia,1983,57(3):397-405.

[29] Lambert S M,Wiens J J.Evolution of viviparity:a phylogenetic test of the cold-climate hypothesis in phrynosomatid lizards[J].Evolution,2013,67(9):2614-2630.

[30] Webb J K,Shine R,Christian K A.The adaptive significance of reptilian viviparity in the tropics:testing the maternal manipulation hypothesis[J].Evolution,2006,60(1):115-122.

[31] Wallman H L,Bennett W A.Effects of parturition and feeding on thermal preference of Atlantic stingray,Dasyatis sabina (Lesueur)[J].Environmental Biology of Fishes,2006,75(3):259-267.

[32] Hight B V,Lowe C G.Elevated body temperatures of adult female leopard sharks,Triakis semifasciata,while aggregating in shallow nearshore embayments:evidence for behavioral thermoregulation?[J].Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology,2007,352(1):114-128.

[33] Larsson D G J,Mayer I,Hyllner S J,et al.Seasonal variations of vitelline envelope proteins,vitellogenin,and sex steroids in male and female eelpout (Zoarces viviparus)[J].General and Comparative Endocrinology,2002,125(2):184-196.

[34] Rasmussen T H,Andreassen T K,Pedersen S N,et al.Effects of waterborne exposure of octylphenol and oestrogen on pregnant viviparous eelpout (Zoarces viviparus) and her embryos in ovario[J].Journal of Experimental Biology,2002,205(24):3857-3876.

[35] Hrbek T,Seckinger J,Meyer A.A phylogenetic and biogeographic perspective on the evolution of poeciliid fishes[J].Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution,2007,43(3):986-998.

[36] Santos R N,Andrade C C,Santos A F,et al.Hystological analysis of ovarian development of the characiform Oligosarcus hepsetus (Cuvier,1829) in a Brazilizn Reservoir[J].Brazilian Journal of Biology,2005,65(1):169-177.

[37] Brown-Peterson N J,Wyanski D M,Saborido-Rey F,et al.A standardized terminology for describing reproductive development in fishes[J].Marine and Coastal Fisheries,2011,3(1):52-70.

[38] Rocha T L,Yamada  T,Costa R M E,et al.Analyses of the development and glycoproteins present in the ovarian follicles of Poecilia vivipara (Cyprinodontiformes,Poeciliidae)[J].Pesquisa Veterinária Brasileira,2011,31(1):87-93.

T,Costa R M E,et al.Analyses of the development and glycoproteins present in the ovarian follicles of Poecilia vivipara (Cyprinodontiformes,Poeciliidae)[J].Pesquisa Veterinária Brasileira,2011,31(1):87-93.

[39] Campuzano-Caballero J C,Uribe M C.Structure of the female gonoduct of the viviparous teleost Poecilia reticulata (Poeciliidae) during nongestation and gestation stages[J].Journal of Morphology,2014,275(3):247-257.

[40] Torres-Martínez A,De Dios L R,Hernández-Franyutti A,et al.Structure of the testis and spermatogenesis of the viviparous teleost Poecilia mexicana (Poeciliidae) from an active sulfur spring cave in Southern Mexico[J].Journal of Morphology,2019,280(10):1537-1547.

[41] Rosenthal G G,Martinez T Y F,De León F J G,et al.Shared preferences by predators and females for male ornaments in swordtails[J].The American Naturalist,2001,158(2):146-154.

[42] Conover D O,Heins S W.Adaptive variation in environmental and genetic sex determination in a fish[J].Nature,1987,326(6112):496-498.

[43] Karayücel ![]() O,Karayücel S.Effect of temperature on sex ratio in guppy Poecilia reticulata (Peters 1860)[J].Aquaculture Research,2006,37(2):139-150.

O,Karayücel S.Effect of temperature on sex ratio in guppy Poecilia reticulata (Peters 1860)[J].Aquaculture Research,2006,37(2):139-150.

[44] 刘灼见,高书堂,邓青.食蚊鱼的性腺发育及性周期研究[J].武汉大学学报:自然科学版,1996,42(4):100-106.

[45] Koya Y,Ishikawa S,Sawaguchi S.Effects of temperature and photoperiod on ovarian cycle in the mosquitofish,Gambusia ajfinis[J].Japanese Journal of Ichthyology,2004,51:43-50.

[46] Cruz-Gómez A,Del Carmen Rodríguez-Varela A,López H V.Reproductive aspects of Girardinichthys multiradiatus,Meek 1904 (Pisces:Goodeidae)[J].Biocyt:Biología,Cienciay Tecnología,2011,4(1):215-228.

[47] Koya Y,Fujita A,Niki F,et al.Sex differentiation and pubertal development of gonads in the viviparous mosquitofish,Gambusia affinis[J].Zoological Science,2003,20(10):1231-1242.

[48] Silva-Santos J R,Martínez-Salda a M C,Rico-Martínez R,et al.Reproductive biology of Goodea atripinnis (Jordan,1880)(Cyprinodontiformes:Goodeidae) under controlled conditions[J].Journal of Experimental Biology and Agricultural Sciences,2016,4(2):180-193.

a M C,Rico-Martínez R,et al.Reproductive biology of Goodea atripinnis (Jordan,1880)(Cyprinodontiformes:Goodeidae) under controlled conditions[J].Journal of Experimental Biology and Agricultural Sciences,2016,4(2):180-193.

[49] Moser H G.Reproduction in the viviparous South African clinid fish Fucomimus mus[J].African Journal of Marine Science,2007,29(3):423-436.

[50] Reznick D,Meredith R,Collette B B.Independent evolution of complex life history adaptations in two families of fishes,live-bearing halfbeaks (Zenarchopteridae,Beloniformes) and Poeciliidae (Cyprinodontiformes)[J].Evolution:International Journal of Organic Evolution,2007,61(11):2570-2583.

[51] Koya Y,Ohara S,Ikeuchi T,et al.The reproductive cycle of female Zoarces elongatus,a viviparous teleost[J].Bulletin of the Hokkaido National Fisheries Research Institute,1993,57:9-20.

[52] Koya Y,Ohara S,Ikeuchi T,et al.Testicular development and sperm morphology in the viviparous teleost,Zoarces elongatus[J].Bulletin of the Hokkaido National Fisheries Research Institute (Japan),1993,57:21-31.

[53] Takemura A,Takano K,Takahashi H.Reproductive cycle of a viviparous fish,the white-edged rockfish,Sebastes taczanowskii[J].Bulletin of the Faculty of Fisheries Hokkaido University,1987,38:111-125.

[54] Kusakari M.Studies on the reproductive biology and artificial juvenile production of kurosoi Sebastes schlegeli[J].Scientific Reports of Hokkaido Fisheries Experimental Station,1995,47:41-124.

[55] Boehlert G W,Kusakari M,Shimizu M,et al.Energetics during embryonic development in kurosoi,Sebastes schlegeli Hilgendorf[J].Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology,1986,101(3):239-256.

[56] Macfarlane R B,Bowers M J.Matrotrophic viviparity in the yellowtail rockfish Sebastes flavidus[J].The Journal of Experimental Biology,1995,198(5):1197-1206.

[57] Takemura A,Takano K,Takahashi H.The uptake of macromolecular materials in the hindgut of viviparous rockfish embryos[J].Journal of Fish Biology,1995,46(3):485-493.

[58] Wourms J P.Reproduction and development of Sebastes in the context of the evolution of piscine viviparity[J].Environmental Biology of Fishes,1991,30(1-2):111-126.

[59] Moore R K,Scott A P,Collins P M.Circulating C-21 steroids in relation to reproductive condition of a viviparous marine teleost,Sebastes rastrelliger (grass rockfish)[J].General and Comparative Endocrinology,2000,117(2):268-280.

[60] Mori H,Nakagawa M,Soyano K,et al.Annual reproductive cycle of black rockfish Sebastes schlegeli in captivity[J].Fisheries Science,2003,69(5):910-923.

[61] Mu Weijie,Wen Haishen,He Feng,et al.Cloning and expression analysis of vasa during the reproductive cycle of Korean rockfish,Sebastes schlegeli[J].Journal of Ocean University of China,2013,12:115-124.

[62] Mu W J,Wen H S,Li J F,et al.Cloning and expression analysis of Foxl2 during the reproductive cycle in Korean rockfish,Sebastes schlegeli[J].Fish Physiology and Biochemistry,2013,39(6):1419-1430.

[63] Mu W J,Wen H S,He Feng,et al.Cloning and expression analysis of follicle-stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone receptor during the reproductive cycle in Korean rockfish (Sebastes schlegeli)[J].Fish Physiology and Biochemistry,2013,39(2):287-298.

[64] Shi Dan,Wen H S,He Feng,et al.The physiology functions of estrogen receptor α (ERα) in reproduction cycle of ovoviviparous black rockfish,Sebastes schlegeli Hilgendorf[J].Steroids,2011,76(14):1597-1608.

[65] Mu W J,Wen H S,Shi D,et al.Molecular cloning and expression analysis of estrogen receptor betas (ERβ1 and ERβ2) during gonad development in the Korean rockfish,Sebastes schlegeli[J].Gene,2013,523(1):39-49.

[66] Baltz D M.Life history variation among female surfperches (Perciformes:Embiotocidae)[J].Environmental Biology of Fishes,1984,10(3):159-171.

[67] Froeschke B,Allen L G,Pondella II D J.Life history and courtship behavior of black perch,Embiotoca jacksoni (Teleostomi:Embiotocidae),from Southern California[J].Pacific Science,2007,61(4):521-531.

[68] LaBrecque J R,Alva-Campbell Y R,Archambeault S,et al.Multiple paternity is a shared reproductive strategy in the live-bearing surfperches (Embiotocidae) that may be associated with female fitness[J].Ecology and Evolution,2014,4(12):2316-2329.

[69] Wilhelm D,Koopman P.The makings of maleness:towards an integrated view of male sexual development[J].Nature Reviews Genetics,2006,7(8):620-631.

[70] Sanger T J,Gredler M L,Cohn M J.Resurrecting embryos of the tuatara,Sphenodon punctatus,to resolve vertebrate phallus evolution[J].Biology Letters,2015,11(10):20150694.

[71] Chambers J.The cyprinodontiform gonopodium,with an atlas of the gonopodia of the fishes of the genus Limia[J].Journal of Fish Biology,1987,30(4):389-418.

[72] 林丹军,尤永隆,陈莲云.卵胎生硬骨鱼褐菖鲉精巢的周期发育[J].动物学研究,2000,21(5):337-342.

[73] 杨艳平,温海深,何峰,等.许氏平鮋精巢的形态结构与发育组织学[J].大连海洋大学学报,2010,25(5):391-396.

[74] Galindo-Villegas J,Sosa-Lima E.Gonopodial system review and a new fish record of Poeciliopsis infans (Cyprinodontiformes:Poeciliidae) for Lake Patzcuaro,Michoacan,central Mexico[J].Revista de Biología Tropical,2002,50(3-4):1151-1157.

[75] Ogino Y,Katoh H,Yamada G.Androgen dependent development of a modified anal fin,gonopodium,as a model to understand the mechanism of secondary sexual character expression in vertebrates[J].FEBS Letters,2004,575(1-3):119-126.

[76] Turner C L.The skeletal structure of the gonopodium and gonopodial suspensorium of Anableps anableps[J].Journal of Morphology,1950,86(2):329-365.

[77] Bisazza A,Rogers L J,Vallortigara G.The origins of cerebral asymmetry:a review of evidence of behavioural and brain lateralization in fishes,reptiles and amphibians[J].Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews,1998,22(3):411-426.

[78] Greven H,Brenner M.How to copulate without an intromittent organ:the external genital structures and mating behaviour of Xenotoca eiseni (Goodeidae)[M]//Uribe-Aranzabal M C,Grier H.Viviparous Fishes II.Homestaed,Florida:New Life Publications,2010:446-450.

[79] Iida A.Male-specific asymmetric curvature of anal fin in a viviparous teleost,Xenotoca eiseni[J].Zoology,2019,134:1-7.

[80] Pavlov D A,Emel’yanova N G.Transition to viviparity in the order Scorpaeniformes:brief review[J].Journal of Ichthyology,2013,53:52-69.

[81] Orr T J,Brennan P L R.Sperm storage:distinguishing selective processes and evaluating criteria[J].Trends in Ecology & Evolution,2015,30(5):261-272.

[82] Koya Y,Munehara H,Takano K.Sperm storage and motility in the ovary of the marine sculpin Alcichthys alcicornis (Teleostei:Scorpaeniformes),with internal gametic association[J].Journal of Experimental Zoology,2002,292(2):145-155.

[83] Koya Y,Munehara H,Takano K.Sperm storage and degradation in the ovary of a marine copulating sculpin,Alcichthys alcicornis (Teleostei:Scorpaeniformes):role of intercellular junctions between inner ovarian epithelial cells[J].Journal of Morphology,1997,233(2):153-163.

[84] Storrie M T,Walker T I,Laurenson L J,et al.Microscopic organization of the sperm storage tubules in the oviducal gland of the female gummy shark (Mustelus antarcticus),with observations on sperm distribution and storage[J].Journal of Morphology,2008,269(11):1308-1324.

[85] Bernal M A,Sinai N L,Rocha C,et al.Long-term sperm storage in the brownbanded bamboo shark Chiloscyllium punctatum[J].Journal of Fish Biology,2015,86(3):1171-1176.

[86] Grier H J,Collette B B.Unique spermatozeugmata in testes of halfbeaks of the genus Zenarchopterus (Teleostei:Hemiramphidae)[J].Copeia,1987,1987(2):300-311.

[87] Olivera-Tlahuel C,Cruz M V S,Moreno-Mendoza N A,et al.Morphological structures for potential sperm storage in poeciliid fishes.Does superfetation matter?[J].Journal of Morphology,2017,278(7):907-918.

[88] Turner C L.Viviparity superimposed upon ovo-viviparity in the Goodeidae,a family of cyprinodont teleost fishes of the Mexican Plateau[J].Journal of Morphology,1933,55(2):207-251.

[89] Mu oz M,Casadevall M,Bonet S,et al.Sperm storage structures in the ovary of Helicolenus dactylopterus dactylopterus(Teleostei:Scorpaenidae):an ultrastructural study[J].Environmental Biology of Fishes,2000,58:53-59.

oz M,Casadevall M,Bonet S,et al.Sperm storage structures in the ovary of Helicolenus dactylopterus dactylopterus(Teleostei:Scorpaenidae):an ultrastructural study[J].Environmental Biology of Fishes,2000,58:53-59.

[90] Moser H G.Seasonal histological changes in the gonads of Sebastodes paucispinis Ayres,an ovoviviparous teleost (family Scorpaenidae)[J].Journal of Morphology,1967,123(4):329-353.

[91] Darling J D S,Noble M L,Shaw E.Reproductive strategies in the surfperches.I.Multiple insemination in natural populations of the shiner perch,Cymatogaster aggregata[J].Evolution,1980,34(2):271-277.

[92] Wiebe J P.The reproductive cycle of the viviparous seaperch,Cymatogaster aggregata Gibbons[J].Canadian Journal of Zoology,1968,46(6):1221-1234.

[93] Nagahama Y,Takemura A,Takano K,et al.Serum steroid hormone levels in relation to the reproductive cycle of Sebastes taczanowskii and S.schlegeli[J].Environmental Biology of Fishes,1991,30(1-2):31-38.

[94] Takemura A,Takano K,Yamauchi K.The in vitro effects of various steroid hormones and gonadotropin on oocyte maturation of the viviparous rockfish,Sebastes taczanowskii[J].Bulletin of the Faculty of Fisheries Hokkaido University,1989,40(1):1-7.

[95] Venkatesh B,Tan C H,Lam T J.Steroid hormone profile during gestation and parturition of the guppy (Poecilia reticulata)[J].General and Comparative Endocrinology,1990,77(3):476-483.

[96] Venkatesh B,Tan C H,Lam T J.Steroid production by ovarian follicles of the viviparous guppy (Poecilia reticulata) and its regulation by precursor substrates,dibutyryl cAMP and forskolin[J].General and Comparative Endocrinology,1992,85(3):450-461.

[97] Venkatesh B,Tan C H,Kime D E,et al.Steroid metabolism by ovarian follicles and extrafollicular tissue of the guppy (Poecilia reticulata) during oocyte growth and gestation[J].General and Comparative Endocrinology,1992,86(3):378-394.

[98] Criscuolo-Urbinati E,Kuradomi R Y,Urbinati E C,et al.The administration of exogenous prostaglandin may improve ovulation in pacu (Piaractus mesopotamicus)[J].Theriogenology,2012,78(9):2087-2094.

[99] Fujimori C,Ogiwara K,Hagiwara A,et al.Expression of cyclooxygenase-2 and prostaglandin receptor EP4b mRNA in the ovary of the medaka fish,Oryzias latipes:possible involvement in ovulation[J].Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology,2011,332(1-2):67-77.

[100] Tan C H,Lam T J,Wong L Y,et al.Prostaglandin synthesis and its inhibition by cyclic AMP and forskolin in postpartum follicles of the guppy[J].Prostaglandins,1987,34(5):697-715.

[101] Venkatesh B,Tan C H,Lam T J.Prostaglandin synthesis in vitro by ovarian follicles and extrafollicular tissue of the viviparous guppy (Poecilia reticulata) and its regulation[J].Journal of Experimental Zoology,1992,262(4):405-413.

[102] Venkatesh B,Tan C H,Lam T J.Prostaglandins and teleost neurohypophyseal hormones induce premature parturition in the guppy,Poecilia reticulata[J].General and Comparative Endocrinology,1992,87(1):28-32.

[103] Munakata A,Kobayashi M.Endocrine control of sexual behavior in teleost fish[J].General and Comparative Endocrinology,2010,165(3):456-468.

[104] Scheepers M J,Gouws G,Gon O.Evidence of multiple paternity in the bluntnose klipfish,Clinus cottoides (Blennioidei:Clinidae:Clinini)[J].Environmental Biology of Fishes,2018,101(12):1669-1675.

[105] Gao Tianxiang,Ding Kui,Song Na,et al.Comparative analysis of multiple paternity in different populations of viviparous black rockfish,Sebastes schlegelii,a fish with long-term female sperm storage[J].Marine Biodiversity,2018,48(4):2017-2024.

[106] Soucy S,Travis J.Multiple paternity and population genetic structure in natural populations of the poeciliid fish,Heterandria formosa[J].Journal of Evolutionary Biology,2003,16(6):1328-1336.