眼睛晶体是头足类重要视觉器官,由前后两个半球组成,其功能与脊椎动物的眼睛晶体相似[1],主要用于辅助捕食和躲避敌害[2],但是头足类与脊椎动物眼睛晶体的生成原理和蛋白质组差异明显[3]。近年来,眼睛晶体越来越受到研究头足类的学者关注,被认为是除耳石、角质颚、内壳之外,又一记录头足类生活史信息的硬组织材料[4-7],尽管它在年龄和生长的研究上不如其他硬组织,但在微化学尤其个体发育期稳定同位素的分析上比其他硬组织更有效、更可靠。为此,本研究中从眼睛晶体的尺寸、微结构、微量元素和稳定同位素等方面,回顾了其在头足类年龄、生长、摄食、栖息和洄游等基础生活史过程中的应用,旨在为中国头足类基础生物与生态学研究提供参考。

1 晶体结构与组成

眼睛晶状体(以下简称晶体)是眼球中重要的屈光装置[8],前后两面交界处为赤道部,两面的顶点分别为晶状体前极、后极。头足类与脊椎动物类似,依靠晶状体前后位置或曲度的变化,进行视觉的调节。晶状体由晶状体囊和晶状体纤维组成。晶状体囊为一透明薄膜,完整地包围在晶状体外面。前囊下有一层上皮细胞,当上皮细胞到达赤道部后,不断伸长、弯曲,移向晶状体内,成为晶状体纤维。晶状体纤维在一生中不断生长,并将旧的纤维挤向晶状体的中心,并逐渐硬化而成为晶状体核,晶状体核外较新的纤维称为晶状体皮质[9]。

2 晶体尺寸

海洋生物眼睛晶体的大小一方面反映晶体自身的生长,另一方面可反映生物个体本身的生长。眼睛晶体的大小(直径和质量)已被尝试用于鱼类的年龄和生长的研究[10-12]。而对头足类眼睛晶体的相关研究开展较少,有学者认为,可通过建立眼睛晶体直径与头足类胴长的关系,或通过分析不同年龄头足类个体的眼睛晶体折射率的变化来研究头足类的生长[13]。Hall[14]分析认为,澳大利亚巨乌贼Sepia apama眼睛晶体的直径和湿质量与雌、雄个体胴长均呈线性关系。Northern[15]分析认为,强壮桑椹乌贼Moroteuthis ingen眼睛晶体的直径和质量与雌、雄个体胴长及雄性个体的体质量呈线性关系,而与雌性个体的体质量呈指数关系,这是因为雌性个体在性成熟后由于性腺的快速发育导致体质量迅速增加,而此时眼睛晶体的生长则非常缓慢。

3 晶体微结构

3.1 晶体切片制作与观察

Baqueiro-Cárdenas等[5]详细介绍了头足类眼睛晶体切片的制作过程与观察方法,Rodríguez-Domínguez等[6]在此基础上进行了改进。切片的制作主要包括固定、脱钙、脱水、冲洗、包埋等5个步骤:(1)固定,用中性福尔马林或70%(体积分数,下同)酒精浸泡晶体72 h;(2)脱钙,用流水冲洗72 h,用脱钙溶液(15%柠檬酸钠和50%甲酸混合溶液)浸泡24 h后,更换脱钙溶液继续浸泡24 h,再用流水冲洗24 h;(3)脱水,在95%酒精溶液中浸泡1.5 h,然后每0.5 h更换1次酒精溶液,连续更换3次后改用100%酒精浸泡,每0.5 h更换一次酒精,连续更换3次;(4)冲洗,用超纯水浸泡0.5 h后更换超纯水再浸泡1 h;(5)包埋,在石蜡溶液中浸泡1 h后,更换溶液继续浸泡1 h,最后再用新鲜的石蜡溶液继续浸泡2 h。

切片染色主要包括失蜡、水化、染色、脱水、冲洗等5个步骤:(1)失蜡,超纯水中浸泡20 min,每10 min换一次超纯水;(2)水化,先用100%酒精浸泡5 min,再用95%酒精浸泡5 min,最后用蒸馏水浸泡10 min;(3)染色,在苏木精溶液中浸泡4 min,然后流水冲洗5 min,并先后在1%磷钼酸溶液和蒸馏水中浸2~3 s,再在伊红溶液中浸泡1 min,然后先后分别在蒸馏水、1%磷钼酸溶液和蒸馏水中浸2~3 s;(4)脱水,在95%酒精中浸泡2 min,再在100%酒精中浸泡4 min,每2 min换一次酒精;(5)冲洗,在超纯水中浸泡10 min,每5 min更换一次超纯水。

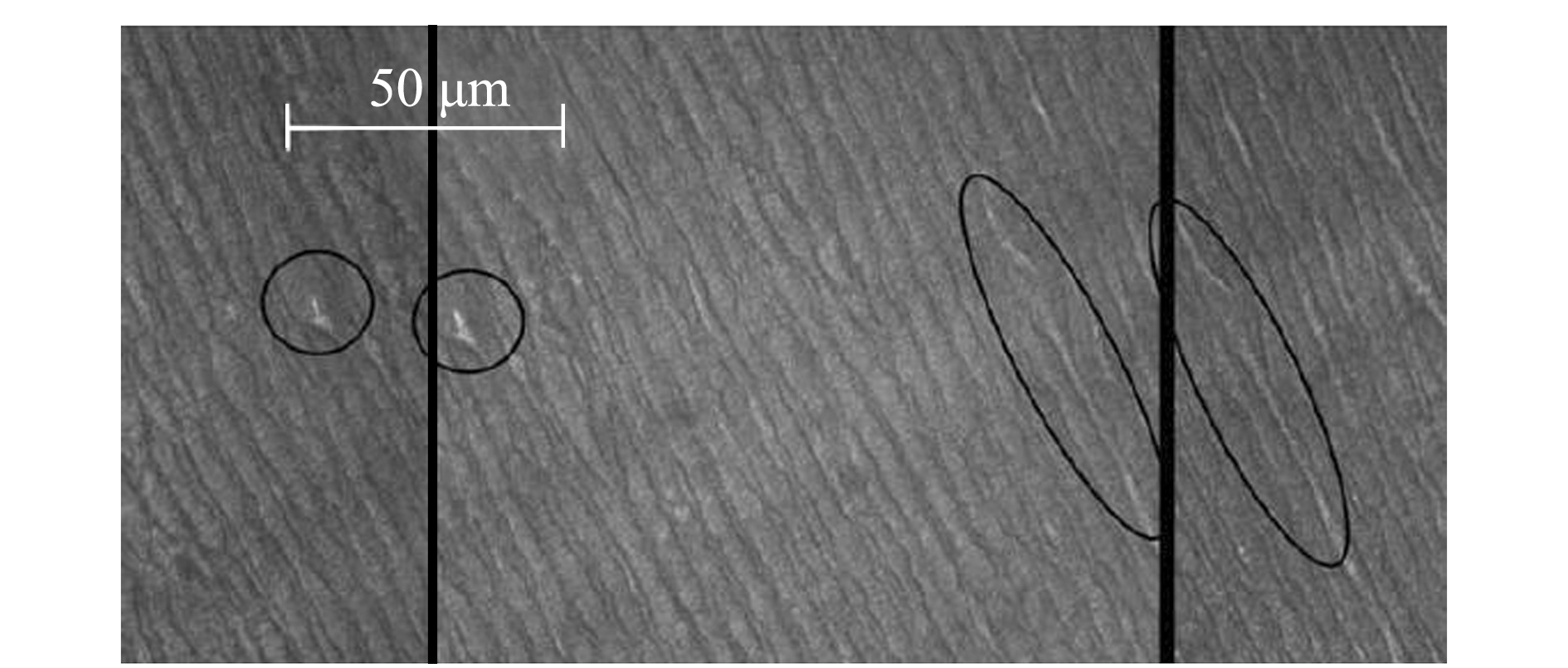

为了方便晶体微结构的观察,将制作好的晶体切片置于载玻片上,用胶头滴管滴上清水;在连接有CCD的显微镜下(400×)对生长纹进行拍照,用图像处理软件对所拍图片进行拼图处理。值得注意的是,在对晶体进行连续拍照时,尽量在相邻的两个视野中至少保持有一个特殊标记(图1),这样可以确保后期图片拼接的准确性[5]。

3.2 晶体微结构在年龄与生长中的应用

头足类眼睛晶体是除耳石、角质颚和内壳以外的少数硬组织之一,它由许多同心的纤维层组成[16]。Willekens等[17]和Clarke[18]先后在几种头足类的眼睛晶体中发现这种同心生长纹结构,然而其形成的周期性主要存在三种不同观点:第一种观点认为,晶体生长纹与头足类实际日龄相符[5,19],根据此假设,Agus等[20]估算地中海撒丁岛海域的枪乌贼Loligo vulgaris和福氏枪乌贼Loligo forbesii的寿命分别为17、18个月;第二种观点认为,晶体生长纹与头足类实际日龄无关[14,21],持这种观点的学者发现,在某些头足类当中,其晶体生长纹远远超过实际日龄;第三种观点认为,晶体生长纹的形成虽然具有周期性,但不是每日一纹,其沉积规律可能依种类和生活环境的不同而变化[6]。

图1 红色肠腕蛸眼睛体图片的拼接示意图[5]

Fig.1 Identifying marks in individual images to integrate a mosaic of eye lens in crystalline structure of octopus Enteroctopus megalocyathus [5]

4 晶体微量元素在栖息环境中的应用

海洋生物的眼睛晶体与耳石、骨骼、鳞片等其他硬组织不同,它的钙化程度为零,不太适合用作微量元素分析[22]。尽管如此,研究者们还是在鱼类眼睛晶体中探测到了Ba、Co、 Cu、Fe、Hg、Mn、Pb、Rb和Sr等微量元素[23],它们与鱼类耳石、鳞片和鳍条中的微量元素种类组成和含量不同[24-26]。Dove等[25]认为,晶体中微量元素的富集与空间环境变化有关,Kingsford等[27]认为,其与水深也存在关系。此外,研究中还发现,作为鱼类耳石中不容易检出的Hg和Pb元素,在眼睛晶体中则易被检出,这可以作为鱼类耳石微量元素研究的一个有力补充[25,27]。Gillanders[26]研究认为,眼睛晶体微量元素可用作鱼类的种群判定。然而,至今未见到关于头足类眼睛晶体微量元素的研究报道。

5 晶体碳氮稳定同位素

5.1 晶体断面取样方法

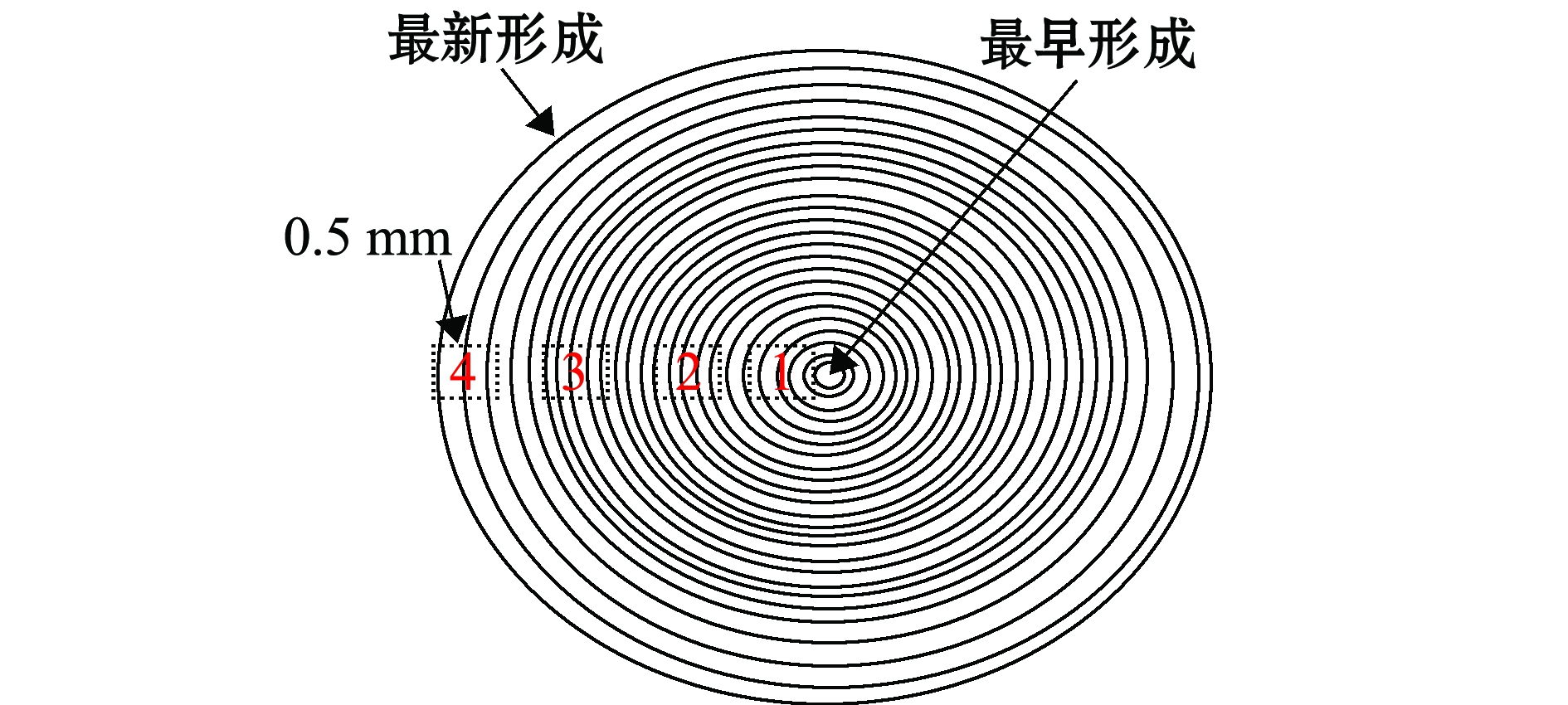

眼睛晶体蛋白质含量可达50%[28],故其比耳石更适合碳(δ13C)氮(δ15N)稳定同位素的分析[29]。一般认为,通过对眼睛晶体不同时间断面碳氮稳定同位素的分析,可以获取头足类不同生活史阶段的摄食生态信息,具体试验方法如下:(1)分离,取出晶体,移除晶体的远端,保留晶体的近端;(2)浸泡,用蒸馏水浸泡近端晶体5 min,使其充分吸水;(3)测量,用游标卡尺测量浸泡处理过的近端晶体的直径;(4)微取样,在解剖镜下,用无水酒精消毒过的宽头镊子,由晶体最外层向晶体核心剥取0.5 mm左右厚的晶体;(5)再测量,用游标卡尺测量剥取晶体后剩余晶体的直径;(6)重复以上步骤(4)和(5)的过程,直至晶体核心部分直径约为0.5 mm,依据晶体大小的不同可获得若干个不同断面的晶体样品。

图2 眼睛晶体取样示意图

Fig.2 Schematic diagram of subsampling in eye lens

5.2 晶体碳氮稳定同位素在摄食生态分析中的应用

传统的稳定同位素法主要采用肌肉分析头足类的摄食生态[30-32],由于肌肉自身新陈代谢的存在,它往往只能反映取样前两个月内的摄食信息[33]。与鱼类的眼睛晶体相似,头足类的眼睛晶体缺少蛋白质的合成和分解,因而几乎不存在新陈代谢作用,即未有蛋白质的更新[16]。因此,眼睛晶体各断面层所包含的稳定同位素信息反映了其形成时的摄食信息,通过对眼睛晶体不同断面稳定同位素的分析,可重建头足类个体发育期的摄食生态史。Parry[34]分析了14尾柔鱼Ommastrephes bartramii和15尾鸢乌贼Sthenoteuthis oualaniensis的眼睛晶体不同断面的δ15N,结果发现,随着个体发育过程中胴长的增加,δ15N不断增加,这说明柔鱼和鸢乌贼捕食饵料的营养级随着个体发育不断上升。Hunsicker[35]和Hunsikcer等[4]利用眼睛晶体的碳氮稳定同位素分析了贝乌贼Berryteuthis magister不同生长阶段的摄食变化,以及在东白令海所处的生态地位。研究结果显示,贝乌贼幼体到成体期营养级上升1级,贝乌贼的食谱不是由饵料大小所决定,而是与该区域其他商业性捕捞鱼类享有共同的食谱范围。

5.3 晶体碳氮稳定同位素在栖息洄游分析中的应用

近年来,基于角质颚和内壳碳氮稳定同位素信息被广泛用于头足类的栖息环境与洄游路线重建[33,36-41]。然而,关于眼睛晶体的相关研究目前仅有一篇报道[7],该研究通过眼睛晶体的碳氮稳定同位素分析了茎柔鱼的起源及其洄游史策略,具体根据眼睛晶体δ13C和δ15N个体间的较大差异推断茎柔鱼的洄游路线比较复杂,并根据眼睛晶体核心层较低的δ13C推断茎柔鱼出生地在37°N以北。

6 展望

由于眼睛晶体生长纹形成周期的不确定性,致使通过眼睛晶体微结构直接研究头足类年龄和生长受到了一定程度的限制,尽管如此,随着基于眼睛晶体放射性同位素碳的年龄鉴定技术在鱼类中的应用[42],在头足类中的相关研究也值得期待。近年来,随着分析手段不断提升,头足类硬组织的微化学尤其碳氮稳定同位素的分析被广泛用于头足类基础生态学研究。尽管角质颚稳定同位素均有一些报道[43-44],但是新生的角质颚无法与旧生的角质颚分开,故无法从时间序列上分析头足类的稳定同位素。此外,角质颚中存在的大量蛋白质、角质和色素也会影响同位素的测定结果[45]。内壳的生长不仅是长度的生长,而且其宽度也在生长[46],因此,从严格意义上来说,沿长度方向的截面不能完全反映头足类不同生长阶段的生态学信息[38-39]。头足类耳石主要成分为碳酸盐(95%),其蛋白质含量较低[47-48],且体积太小,因此,不适合用于碳氮稳定同位素的分析,但适合用作微量元素分析[49-51]。头足类眼睛晶体与以上这几种硬组织相比,在稳定同位素的测定上有着明显的优势。首先,眼睛晶体体积较大(直径为10~20 mm),能够满足稳定同位素的测定;其次,眼睛晶体是一层一层的包裹式生长,很容易剥落,因此,可以从时间序列上准确的分析头足类的生活史信息。今后的研究中需要对比头足类耳石年龄,准确掌握眼睛晶体各层断面形成的确切时间,进而重建头足类的栖息、洄游和摄食等生活史信息。

[1] Packard A.Cephalopods and fish:the limits of convergence[J].Biological Reviews,1972,47(2):241-307.

[2] Nilsson D E,Warrant E J,Johnsen S,et al.A unique advantage for giant eyes in giant squid[J].Current Biology,2012,22(8):683-688.

[3] Brahma S K.Ontogeny of lens crystallins in marine cephalopods[J].Journal of Embryology and Experimental Morphology,1978,46:111-118.

[4] Hunsicker M E,Essington T E,Aydin K Y,et al.Predatory role of the commander squid Berryteuthis magister in the eastern Bering Sea:insights from stable isotopes and food habits[J].Marine Ecology Progress Series,2010,415:91-108.

[5] Baqueiro-Cárdenas E R,Correa S M,Guzman R C,et al.Eye lens structure of the octopus Enteroctopus megalocyathus:evidence of growth[J].Journal of Shellfish Research,2011,30(2):199-204.

[6] Rodríguez-Domínguez A,Rosas C,Méndez-Loeza I,et al.Validation of growth increments in stylets,beaks and lenses as ageing tools in Octopus maya[J].Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology,2013,449:194-199.

[7] Onthank K L.Exploring the life histories of cephalopods using stable isotope analysis of an archival tissue[D].Washington:Washington State University,2013.

[8] 孔繁瑶,蔡宝祥.兽医大辞典[M].北京:中国农业出版社,1999:187.

[9] Land M F,Nilsson D E.Animal Eyes[M].New York:Oxford University Press,2002:83-86.

[10] Crivelli A.The eye lens weight and age in the common carp,Cyprinus carpio L.[J].Journal of Fish Biology,1980,16(5):469-473.

[11] Jawad L A.Ocular lens diameter and weight as age indicators in two teleost fishes collected from the Red Sea of Yemen[J].Zoology in the Middle East,2003,29(1):59-62.

[12] Jawad L,Al-Mamry J,Al-Hassani L,et al.The feasibility of using eye lens diameter and weight as an age indicator in the Indian mackerel Rastrelliger kanagurta (Cuvier,1817) collected from the sea of Oman[J].Water Research and Management,2012,2(3):43-46.

[13] Sivak J G,West J A,Campbell M C.Growth and optical development of the ocular lens of the squid (Sepioteuthis lessoniana)[J].Vision Research,1994,34(17):2177-2187.

[14] Hall K C.The life history and fishery of a spawning aggregation of the giant Australian cuttlefish Sepia apama[D].Adelaide:University of Adelaide,2002.

[15] Northern T J.Investigating the post mortem applications of hard parts from two common New Zealand squid species:Onykia ingens and Nototodarus suoanii[D].Dunedin:University of Otago, 2017.

[16] West J A,Sivak J G,Doughty M J.Microscopical evaluation of the crystalline lens of the squid (Loligo opalescens) during embryonic development[J].Experimental Eye Research,1995,60(1):19-35.

[17] Willekens B,Vrensen G,Jacob T,et al.The ultrastructure of the lens of the cephalopod Sepiola:a scanning electron microscopic study[J].Tissue and Cell,1984,16(6):941-950.

[18] Clarke M R.Age determination and common sense[M]//Okutani T,O’Dor R K,Kuborera T.Recent Advances in Cephalopod Fisheries Biology.Tokyo:Tokai University Press,1993:670-678.

[19] O’Shea S.Estimating age and growth rate in Architeuthis dux[D].Auckland:Auckland University of Technology,1998.

[20] Agus B,Mereu M,Cannas R,et al.Age determination of Loligo vulgaris and Loligo forbesii using eye lens analysis[J].Zoomorphology,2017,doi:10.1007/s00435-017-0381-8.

[21] Bettencourt V.Idade e crescimento do choco,Sepia officinalis (Linnaeus, 1758)[D].Portugal:University of Algarve,2000.

[22] Tzadik O E,Curtis J S,Granneman J E,et al.Chemical archives in fishes beyond otoliths:a review on the use of other body parts as chronological recorders of microchemical constituents for expanding interpretations of environmental,ecological,and life-history changes[J].Limnology and Oceanography Methods,2017,15(3):238-263.

[23] Kuck J F R Jr.Composition of the lens[M]//Bellows J G.Cataract and Abnormalities of the Lens.New York,San Francisco,London:Grune & Stratton Inc.,1974.

[24] Dove S G.The incorporation of trace metals into the eye lenses and otoliths of fish[D].Sydney:University of Sydney,1997.

[25] Dove S G,Kingsford M J.Use of otoliths and eye lenses for measuring trace-metal incorporation in fishes:A biogeographic study[J].Marine Biology,1998,130(3):377-387.

[26] Gillanders B M.Trace metals in four structures of fish and their use for estimates of stock structure[J].Fishery Bulletin,2001,99(3):410-419.

[27] Kingsford M J,Gillanders B M.Variation in concentrations of trace elements in otoliths and eye lenses of a temperate reef fish,Prama microlepis,as a function of depth,spatial scale,and age[J].Marine Biology,2000,137(3):403-414.

[28] De Jong W W.Evolution of lens and crystallins[M]//Bloemendal H.Molecular and Cellular Biology of the Eye Lens.New York:John Wiley,1981:221-278.

[29] Wallace A A,Hollander D J,Peebles E B.Stable isotopes in fish eye lenses as potential recorders of trophic and geographic history[J].PLoS One,2014,9(10):e108935.

[30] Ruiz-Cooley R I,Gendron D,Aguí iga S,et al.Trophic relationships between sperm whales and jumbo squid using stable isotopes of C and N[J].Marine Ecology Progress Series,2004,277:275-283.

iga S,et al.Trophic relationships between sperm whales and jumbo squid using stable isotopes of C and N[J].Marine Ecology Progress Series,2004,277:275-283.

[31] Parry M.Trophic variation with length in two ommastrephid squids,Ommastrephes bartramii and Sthenoteuthis oualaniensis[J].Marine Biology,2008,153(3):249-256.

[32] Miller T W,Bosley K L,Shibata J,et al.Contribution of prey to Humboldt squid Dosidicus gigas in the northern California Current,revealed by stable isotope analyses[J].Marine Ecology Progress Series,2013,477:123-134.

[33] Ruiz-Cooley R I,Balance L T,McCarthy M D.Range expansion of the jumbo squid in the NE Pacific:δ15N decrypts multiple origins,migration and habitat use[J].PLoS One,2013,8(3):e59651.

[34] Parry M P.The trophic ecology of two ommastrephid squid species,Ommaterphes bartramii and Sthenoteuthis oualaniensis,in the North Pacific Sub-tropical gyre[D].Hawaii:University of Hawaii,2003.

[35] Hunsicker M E.Evaluating the role of cephalopods within marine food webs and fisheries[D].Washington:University of Washington,2009.

[36] Cherel Y,Ridoux V,Spitz J,et al.Stable isotopes document the trophic structure of a deep-sea cephalopod assemblage including giant octopod and giant squid[J].Biology Letters,2009,5(3):364-367.

[37] Guerra  ,Rodríguez-Navarro A B,González

,Rodríguez-Navarro A B,González  F,et al.Life-history traits of the giant squid Architeuthis dux revealed from stable isotope signatures recorded in beaks[J].ICES Journal of Marine Science,2010,67(7):1425-1431.

F,et al.Life-history traits of the giant squid Architeuthis dux revealed from stable isotope signatures recorded in beaks[J].ICES Journal of Marine Science,2010,67(7):1425-1431.

[38] Ruiz-Cooley R I,Villa E C,Gould W R.Ontogenetic variation of δ13C and δ15N recorded in the gladius of the jumbo squid Dosidicus gigas:geographic differences[J].Marine Ecology Progress Series,2010,399:187-198.

[39] Lorrain A,Argüelles J,Alegre A,et al.Sequential isotopic signature along gladius highlights contrasted individual foraging strategies of jumbo squid (Dosidicus gigas)[J].PloS One,2011,6(7):e22194.

[40] Guerreiro M,Phillips R A,Cherel Y,et al.Habitat and trophic ecology of Southern Ocean cephalopods from stable isotope analyses[J].Marine Ecology Progress Series,2015,530:119-134.

[41] Seco J,Roberts J,Ceia F R,et al.Distribution,habitat and trophic ecology of Antarctic squid Kondakovia longimana and Moroteuthis knipovitchi:inferences from predators and stable isotopes[J].Polar Biology,2016,39(1):167-175.

[42] Nielsen J,Hedeholm R B,Heinemeier J,et al.Eye lens radiocarbon reveals centuries of longevity in the Greenland shark (Somniosus microcephalus)[J].Science,2016,353(6300):702-704.

[43] Cherel Y,Hobson K A.Stable isotopes,beaks and predators:a new tool to study the trophic ecology of cephalopods,including giant and colossal squids[J].Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences,2005,272(1572):1601-1607.

[44] Ruiz-Cooley R I,Markaida U,Gendron D,et al.Stable isotopes on jumbo squid (Dosidicus gigas) beaks to estimate its trophic position:comparison between stomach contents and stable isotopes[J].Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom,2006,86(2):437-445.

[45] Miserez A,Schneberk T,Sun C J,et al.The transition from stiff to compliant materials in squid beaks[J].Science,2008,319(5871):1816-1819.

[46] Arkhipkin A I,Perez J A A.Life history reconstruction[C]//Rodhouse P G,Dawe E G,O’Dor R K.Squid recruitment dynamics:the genus Illex as a model,the commercial Illex species.Influences on variability.Rome:FAO,1998:157-180.

[47] Bettencourt V,Guerra A.Growth increments and biomineralization process in cephalopod statoliths[J].Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology,2000,248(2):191-205.

[48] Radtke R L.Chemical and structural characteristics of statoliths from the short-finned squid Illex illecebrosus[J].Marine Biology,1983,76(1):47-54.

[49] Liu B L,Chen X J,Chen Y,et al.Trace elements in the statoliths of jumbo flying squid off the Exclusive Economic Zones of Chile and Peru[J].Marine Ecology Progress Series,2011,429:93-101.

[50] Liu B L,Chen X J,Chen Y,et al.Geographic variation in statolith trace elements of the Humboldt squid,Dosidicus gigas,in high seas of Eastern Pacific Ocean[J].Marine Biology,2013,160(11):2853-2862.

[51] Liu B L,Chen Y,Chen X J.Spatial difference in elemental signatures within early ontogenetic statolith for identifying Jumbo flying squid natal origins[J].Fisheries Oceanography,2015,24(4):335-346.